Neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) are medical conditions characterized by the progressive degradation of cells in the brain, spinal cord and nerves. Over time, these diseases cause a decline in varying mental and physical functions, such as memory and cognitive deficits or a loss of voluntary muscle control and an inability to move parts of the body.

Past studies showed that both ALS and FTD are associated with the dysfunction of the TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43). In patients diagnosed with these diseases, this protein was found to abnormally accumulate in the cytoplasm (i.e., the gelatinous liquid that fills the inside of cells), while being depleted from the nucleus (i.e., the “control center” of cells that contains their genetic material).

The link between this pattern of TDP-43 accumulation and some neurodegenerative diseases is now well-documented. However, the molecular processes via which this protein regulates the RNA of the patient and contributes to progression of these diseases have not yet been fully elucidated.

Two research teams at Stanford University and University College London (UCL)Nature Neuroscience, suggest that this loss of TDP-43 could influence a mechanism known as alternative polyadenylation (APA), which plays a key role in the expression of genes and the function of proteins.

“Our project emerged from a critical gap in understanding how TDP-43 dysfunction affects RNA processing in ALS and FTD. TDP-43 is a master editor of RNA in cells,” Yi Zeng, researcher at Stanford and co-author of the first paper, told Medical Xpress.

“In ALS and FTD, it leaves the nucleus and forms toxic clumps in the cytoplasm of degenerating neurons. Recent breakthroughs showed this causes splicing defects, where the missing editor fails to remove unwanted sections from RNA messages. This affects important genes like STMN2 and UNC13A; our lab co-discovered the splicing defects in UNC13A.”

In addition to this widely investigated function, the protein TDP-43 is known to have other functions that remain less investigated in the context of neurodegeneration. Some earlier studies had found that this protein helps to determine where RNA “messages” will end, via polyadenylation.

“Think of it like deciding where to put the period at the end of a sentence—put it in the wrong place and you completely change the meaning,” said Zeng. “Where an RNA ends determines its stability, localization, how much protein gets made, and even what kind of protein gets made, so different ending points can completely change a gene’s output.”

The approach employed by the Stanford team

Both the team at Stanford and the one at UCL drew inspiration from earlier works suggesting that polyadenylation processes are somewhat disrupted in neurodegenerative diseases and that this could be linked to the abnormal accumulation of TDP-43.

“For instance, when TDP-43 is lost, STMN2 RNA not only includes unwanted sections but also ends prematurely,” said Zeng. “Our primary objectives were to systematically map how many genes show altered polyadenylation when TDP-43 is lost and understand the molecular rules governing how TDP-43 binding controls where RNAs end. In addition, we set out to validate these changes in patient tissue and determine whether these changes affect protein behavior in disease-relevant ways.”

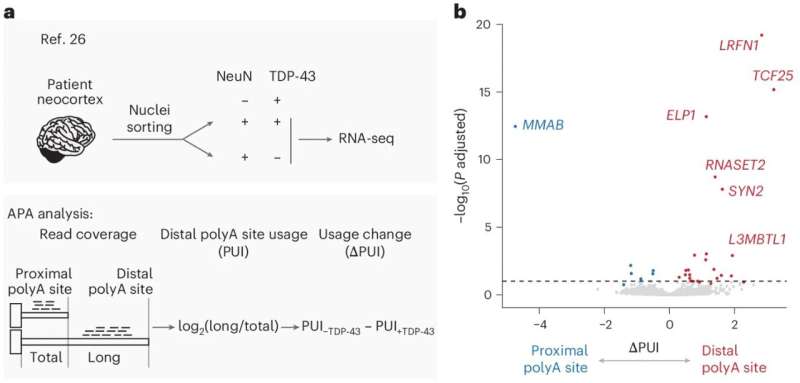

To perform their experiments, Zeng and his colleagues used a combination of techniques to map how the loss of TDP-43 in nuclei affects cell APA processes. First, they analyzed publicly available datasets collected from patients with ALS or FTD, specifically looking for hints of altered polyadenylation.

“We then used human stem cell-derived neurons where we could reduce TDP-43 levels to mimic disease, directly comparing normal and TDP-43-deficient neurons,” explained Zeng. “Because standard RNA sequencing isn’t designed to map polyadenylation sites precisely, we employed specialized 3′ end sequencing that maps exactly where each RNA molecule ends at single-nucleotide resolution.”

As part of their experiments, the researchers also knocked down the TDP-43 protein in neurons and used a technique known as 3′ end sequencing to map all polyadenylation sites across the genome. Using computational tools, they identified sites that were altered by the loss of TDP-43 and combined their observations with data collected by earlier studies.

“Importantly, we validated our findings in patient samples, confirming these polyadenylation changes occur in actual patients, not just models,” added Zeng. “For select genes like TMEM106B, a known FTLD-TDP risk gene, we performed functional studies showing that altered 3′ UTR lengths from polyadenylation changes affect protein production levels, demonstrating real biological consequences.”

The approach employed by the UCL team

For their paper, researchers at UCL studied the link between TDP-43 loss and APA processes using similar methods to those employed by the team at Stanford. First, they developed a new bioinformatic framework that allowed them to identify various APA sites.

They then examined pluripotent stem cell-derived neurons in which TDP-43 was depleted, looking for APA alterations in these cells. This allowed them to pin-point APA sites around which TDP-43 binding occurred and shed light on how the protein regulates the selection of these sites.

Similarly to the team at Stanford, these researchers also set out to investigate whether the APA changes were also evident in tissue extracted from individuals with ALS or FTD post-mortem. They also used techniques known as RNA-sequencing, SLAM-sequencing and ribosome profiling to shed further light on the effects of TDP-43 on specific aspects of APA.

Impact of TDP-43 loss on alternative polyadenylation

The two studies concurrently carried out by the research team at UCL and by Zeng and his colleagues at Stanford offer important new insight into the molecular underpinnings of both ALS and FTD. Specifically, the researchers showed that the loss of TDP-43 in nuclei causes polyadenylation defects in hundreds of genes.

“We uncovered an entirely new dimension of RNA misprocessing in ALS and FTD,” said Zeng. “These changes were found to occur in patients, establishing polyadenylation dysregulation as a bona fide disease feature. TDP-43 binding strength and position determine its effect, with TDP-43 acting like a guard blocking inappropriate ending sites that get used when it’s gone.”

The researchers also showed that the altered polyadenylation of the gene TMEM106B following TDP-43 loss impaired the production of proteins. Notably, variations in this gene were previously linked to a greater risk of developing FTD.

“Importantly, three independent labs published similar findings simultaneously using different approaches, including the team at UCL and another research group at UC Irvine,” said Zeng. “We now have a more complete picture of TDP-43 dysfunction: both splicing and polyadenylation defects affecting hundreds of genes critical for neuron survival. These polyadenylation changes could help detect TDP-43 pathology, track disease progression, and measure therapeutic response, addressing a key field need.”

Therapeutic implications and future research directions

The recent work by these independent research teams could potentially inform the development of future treatments for ALS, FTD and potentially other neurodegenerative diseases. While translating their findings into therapeutic strategies could take time, their papers offer a comprehensive map that could guide further studies focusing on how TDP-43 loss contributes to neurodegeneration.

“As TDP-43 pathology occurs across ALS, FTD, certain Alzheimer’s forms, and other conditions, understanding polyadenylation dysregulation may have broad implications across this spectrum of diseases,” said Zeng. “We are pursuing several research directions that will allow us to move from discovery to patient impact.

“First, we must distinguish drivers from passengers. Not all hundreds of polyadenylation changes necessarily contribute to disease, so we need to determine which drives neurodegeneration by testing whether correcting specific events improves neuron survival and identifying which appear earliest in disease progression.”

In their next studies, the researchers are planning to also explore the impact of TDP-43 loss on different types of cells and across varying neurodegenerative diseases. For instance, they could investigate whether motor neurons exhibit different alterations than cortical neurons, which could ultimately be linked to the distinct symptoms of ALS, FTD and some types of Alzheimer’s disease.

“As part of our next studies, we will also try to determine if these changes track disease progression or measure therapeutic response. This work is already underway,” said Zeng.

The development of pharmaceutical drugs aimed at preventing or reversing the effects of the APA alterations uncovered by the researchers will take some time. Nonetheless, upcoming studies could pin-point genes and pathways that are most affected by TDP-43 loss, which could be promising therapeutic targets.

“Our mechanistic insights into how TDP-43 controls polyadenylation may also inform strategies to compensate for its loss,” added Zeng. “The overarching goal is to use this more complete understanding of TDP-43 dysfunction to develop tools that help patients.”