The health benefits of nature are well-known, but its role in encouraging day-to-day physical activity across different regions and demographics has been less clear. This question carries new urgency as the world faces a “physical inactivity pandemic,” with trends especially stark in the United States, where many people fall short of recommended activity levels.

To investigate how urban green spaces influence movement, researchers with the Stanford-based Natural Capital Project (NatCap), a global alliance focused on valuing nature’s benefits to people, analyzed wearable step-counter data in their new study published in Nature Health. They found that higher park accessibility, not simply more greenery, is associated with higher daily activity.

“Greenness alone doesn’t seem to encourage movement,” said Youngeng Lu, lead author of the paper, who did the work while he was a postdoctoral scholar at NatCap. “Even if you have lots of trees or vegetation, if you can’t easily reach them, it doesn’t translate to more physical activity. Accessibility to parks was the factor that mattered most.”

Measuring movement at scale

Past research links nature to physical activity, but many studies rely on self-reported data, focus on only a few cities, or track people for short periods. Those constraints limit how broadly the findings can be applied.

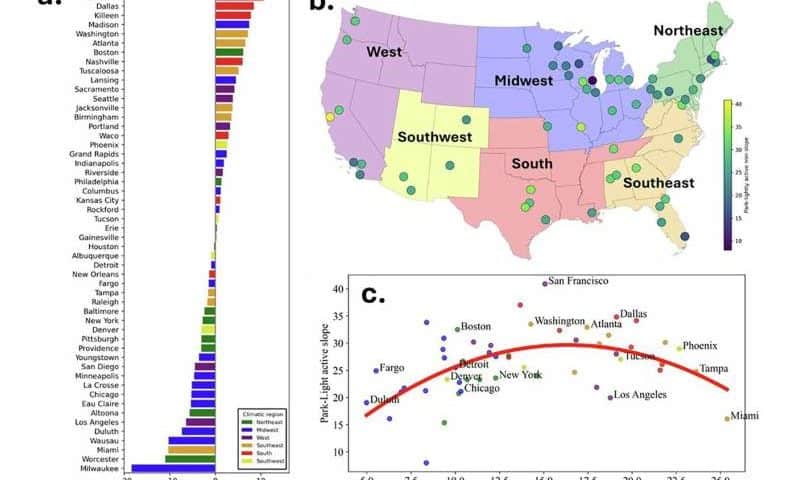

To take the next step in understanding these patterns, the team used multi-year wearable-device data from the All of Us Research Program, a national health initiative. Participants volunteered their Fitbit records, giving researchers three years of daily step counts and activity intensity from 7,013 anonymous users in 53 U.S. metropolitan areas. The team then used modeling that accounted for variations between individual people and cities to test how activity levels shifted with different types of urban nature.

The researchers distinguished between two aspects of urban nature: total greenness (measured from satellite imagery and including forests, gardens, and other vegetation) and park accessibility, which encompasses park existence, distance from population centers, and connectivity to one another. Using participants’ home locations, the team calculated how easy it is for residents to travel to nearby parks on foot.

Although overall greenness didn’t appear to be linked with higher physical activity, park accessibility was a strong predictor of movement. A 10% increase in park accessibility corresponded to roughly 107 additional steps per day.

Who benefits most?

The multi-year dataset allowed researchers to examine how the benefits of park access vary by region and demographic group over time. They also considered variables such as temperature, precipitation, population density, city walkability, and air quality, revealing some telling patterns in the game of step tracking.

Western and southern cities showed stronger links between park accessibility and movement, a trend the team suspects may be influenced by climate, culture, or outdoor habits. Lu emphasized the significant role temperature played in daily step counts. In mild climates, park accessibility had a much stronger effect on physical activity than in cities that are extremely hot or cold, where conditions are less favorable for outdoor exercise.

Demographic trends were also clear. Non-white residents, older adults, and people who were less active at baseline experienced the greatest increase in activity when parks were easier to reach. These results support the “equigenic effect,” in which improved access to green space disproportionately benefits more vulnerable communities.

“For non-white and lower-income neighborhoods, even small increases in park accessibility can encourage significantly more activity,” Lu said. “Parks need to be accessible to everyone, not just higher-income, white populations.”

Designing healthier cities

The study suggests that building new parks isn’t the only way for cities to increase the physical activity of their residents. Enhancing access to existing parks by improving walkability, removing barriers, and connecting parks to nearby neighborhoods (such as creating pedestrian overpasses) can also deliver public health benefits.

“It’s promising from a health perspective,” said Lisa Mandle, senior author on the paper, and director of science-software integration and lead scientist with NatCap. “Investing in access helps residents be more active and promotes equity in urban health.”

Lu added that the priority now is ensuring that the benefits of park access are shared equitably across cities. Future research could track changes in accessibility over time, incorporate GPS data to measure actual park use, and recruit more diverse participants to strengthen the evidence.

By continuing to explore nature’s role in public health, the team hopes to “inform urban planning decisions and inspire interventions that make cities healthier, greener, and more equitable for everyone,” Lu said.

“This study arose out of our efforts to understand how parks and nature in cities can benefit the people living there,” said Mandle. “We know green spaces provide mental health benefits, but we wanted to look more closely at physical activity, and specifically, who benefits most and in what contexts.”

This aligns with the broader goals of NatCap: “to advance understanding of the diversity of ways that nature benefits people in order to incorporate these values into decision-making,” Mandle said.