Compensation for not-for-profit hospital executives and administrators climbed at a higher rate over a 10-year period than those for surgeons, physicians and nurses, according to a national study released in August.

The study in Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research measured trends in compensation from 2005 to 2015, which includes several years in which healthcare systems were affected by the Great Recession and major regulatory changes.

The study provides a different review of healthcare executive compensation, which typically has been focused on comparison with rank-and-file workers and with corporate executives.

Researchers looked at 22 major nonprofit healthcare systems, including 15 academic medical centers. Duke University Health System was the only system involved that’s based in North Carolina.

Adjusted for inflation, average compensation for chief executives at the 22 systems increased from $1.6 million in 2005 to $3.1 million in 2015 — a 93 percent increase, according to the report.

The main reason why fiscal 2015 data is the latest used by the researchers is that most not-for-profit health systems, including Cone Health, Novant Health Inc. and Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center in the Triad, typically report executive compensation to the Internal Revenue Service between 12 and 18 months after the completion of their fiscal years.

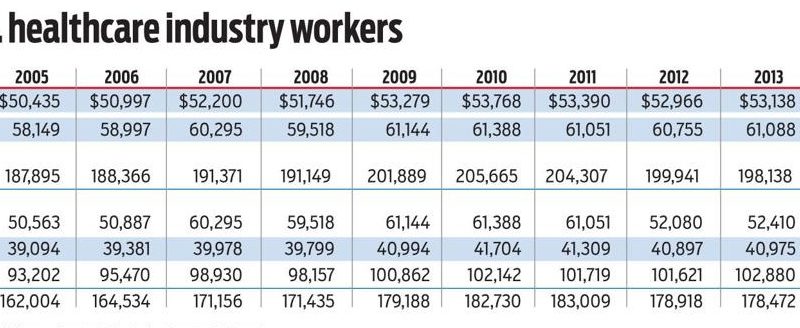

During the same 10-year period, compensation rose by 26 percent for orthopaedic surgeons, 15 percent for pediatricians and 3 percent for registered nurses — the three main employment groups serving as measuring sticks.

Not-for-profit hospital chief executives went from making three times more than orthopaedic surgeons in 2005 to five times more in 2015.

There were even larger increases in the wage gap between chief executives and pediatricians (going from seven times to 12 times) and between chief executives and registered nurses (23 times to 44 times).

Chief financial officers also had higher increased compensation rates — 2.2 times that of orthopaedic surgeons, 5 times of pediatricians and 19 times of registered nurses.

“There is a fast-rising wage gap between the top executives of major nonprofit centers and physicians that reflects the substantial, and growing, cost-burden of management and nonclinical worker wages on the U.S. healthcare system,” said Dr. Randall Marcus with University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center/Case Western Reserve University.

Researchers determined “it is common practice for nonprofit hospital boards, through hospital human resource departments, to annually contract groups to rationalize the fair market value compensation of high-level hospital administrators.

“However, there is conflicting incentive for consultants to recommend compensation increases for these hospital administrators, as this will incentivize subsequent renewal of the consulting engagement.”

By comparison, corporate boards typically measure executive compensation packages by their peers, which also tend to trend upward each year.

Novant

The executive compensation trends found by researchers have some local echoes, particularly with Novant.

Novant listed in its 2016 filing with the IRS that it had 11 employees receiving at least $1 million in total compensation, the breakdown being eight administrators and three doctors.

Carl Armato, chief executive and president of Novant, received a 3.1 percent increase in salary to $1.35 million from 2015 to 2016, as well as a 38.3 percent jump in incentive pay to $1.41 million. Total compensation was up a 16.6 percent increase to $3.43 million.

Total compensation includes retirement contributions, nontaxable benefits, such as life and health insurance premium expenses, and accounting accruals for deferred compensation.

Since Armato took over as Novant’s top executive in 2012, his salary has increased 92.5 percent as top executive, or from $699,113 to $1.35 million, with total compensation rising from $2.79 million to $3.43 million.

By comparison, Dr. Thomas Zweng, Novant’s chief medical officer, made $564,485 in salary in 2016, along with $490,125 in incentive pay. Total compendation was $1.32 million in 2016, up 15.7 percent from 2015. Salary was up 4.5 percent and incentive pay 37.9 percent.

Wake Forest Baptist

The comparisons for Wake Forest Baptist are more complex given the high number of doctors serving as administrators at the academic medical center.

Because of the delay in how Wake Forest Baptist reports compensation to the IRS, how much Dr. Julie Ann Freischlag, the system’s current chief executive and medical school dean, made in 2017 likely won’t become public until May 2019.

For Wake Forest Baptist’s former chief executive Dr. John McConnell, who maintained a urology practice, his base salary rose slightly from 2014 to 2016 as the system recovered from significant financial software and bill-collecting challenges related to implementing its electronic health-records system.

McConnell’s salary went from $996,889 in 2014 to just more than $1 million in 2016. Total compensation was $2.28 million for 2016, compared with $1.78 million in 2015 and $1.75 million in 2014.

Accounting for the jump in McConnell’s total compensation was complicated, primarily because of how not-for-profits report deferred compensation that executives may not obtain for years, if ever.

McConnell received $434,548 in incentives, down from $458,633 in 2015. He did not received incentive pay in fiscal years 2013 and 2014 as part of an overall cost-cutting initiative.

The value of McConnell’s other reportable compensation was $569,856, unchanged from 2015. The vast majority of that compensation is vested supplemental executive retirement plan contribution valued at $546,312. He also received $247,313 in retirement and deferred compensation that includes unvested supplemental executive retirement plan contributions.

The Wake Forest Baptist board of directors approved the supplemental executive retirement plan in January 2012 as part of “implementing of a new executive compensation policy creating consistency across” all of its executives.

The top compensated physician at Wake Forest Baptist for 2016 was Dr. Ross Ungerleider, chief of the pediatric heart program, who was paid $854,892 in salary (up 5.8 percent from 2014), $145,620 in incentive pay (down 43.5 percent), other reportable compensation of $739,128 (up from $19,786). Total compensation was $1.77 million (up 39.7 percent).

Compensation debate

Hospital management pay has become a hot-button issue in recent years, particularly as Forsyth and Wake Forest Baptist medical centers have cut or outsourced hundreds of jobs in response to regulatory changes, as well as the economic downturn and its impact on revenue, charity care and bad debt.

Critics say not-for-profit hospital systems use their nonprofit status for tax advantages and public-relations purposes even as they pay corporate-level wages and benefits to top executives.

Wake Forest Baptist has said the compensation for McConnell and the other top executives is justified because academic medical centers “are very complex organizations that require a special set of skills and experience to manage relationships with physicians and researchers, the university, its patients and community.”

It said the complexity “takes proven talents possessed by a small group of health care executives.”

Novant’s board of trustees has cited over several years that high compensation levels are necessary to recruit and retain executives to run “a very complex organization.”

“Compensation must be considered ‘reasonable’ and within an acceptable range compared to similar organizations,” Novant said.

Impact of tax reform

Dr. Roy Poses, a clinical associate professor of medicine at Brown University in Providence, R.I., and a former physician at three academic medical centers, writes a blog called “Health Care Renewal” in which he frequently tackles the issue of executive compensation.

“When health care organizations are asked to justify their executives’ compensation, they invoke the same talking points: that these payments are necessary to retain executives; that the executives are brilliant and doing extremely hard jobs; and the compensation is set by the market,” Poses said.

“All three points have been debunked, at least when used to justify the compensation of executives in big, for-profit companies.

“Yet rarely are the talking points challenged when used to justify hospital executives’ pay.”

The federal tax reform bill that went into effect in January may play a slowing role in not-for-profit and nonprofit executive compensation increases, said Elliot Dinkin, president and chief executive of Cowden Associates, a Pittsburgh-based specialist in risk management and compensation plans.

The law imposes a 21 percent excise tax on nonprofit employers for salaries of more than $1 million.

Although it was aimed mostly as reining in higher education salaries, such as coaches and university chancellors, it also is projected to have an impact on not-for-profit hospitals nationwide.

“In an environment in which every dollar counts, nonprofit boards will need to justify that it is worthwhile to pay the additional excise tax rather than cut back on salary,” Dinkin said.

Dinkin suggested that nonprofits may want to develop more attractive non-salary related opportunities having to do with time and lifestyle.

“There are effective ways to strike a balance between what’s reasonable and what’s necessary in the competition for talent,” he said.

Growth in value?

Study researchers determined that national healthcare expenditures increased from $2.5 trillion in 2005 to $3.2 trillion in 2015, with wages accounting for more than 25 percent of the growth.

“While the study can’t comment on the value of these executives, managers and other nonclinical workers, the growth in costs appears to outpace plausible growth in value,” Marcus said.

“It appears unlikely to us that the near-doubling of mean compensation to hospital executives is justified by the value added by their work.”

In 2015, there were 10 nonclinical workers and one management official for every one physician, the researchers said.

That ratio has a socioeconomic impact in playing a role in higher healthcare costs.

“We found that a substantial portion of the growth in cost-burden of healthcare worker wages stemmed from management and nonclinical workers,” according to the report.

“Although the number of healthcare workers grew 20 percent from 2005 to 2015, physicians comprised only 5 percent of that growth.

“Therefore, the value of every nonclinical healthcare worker should be evaluated … efforts should be made to align incentives and decrease administrative complexity to improve productivity and reduce costs associated with non-revenue generating healthcare workers.”