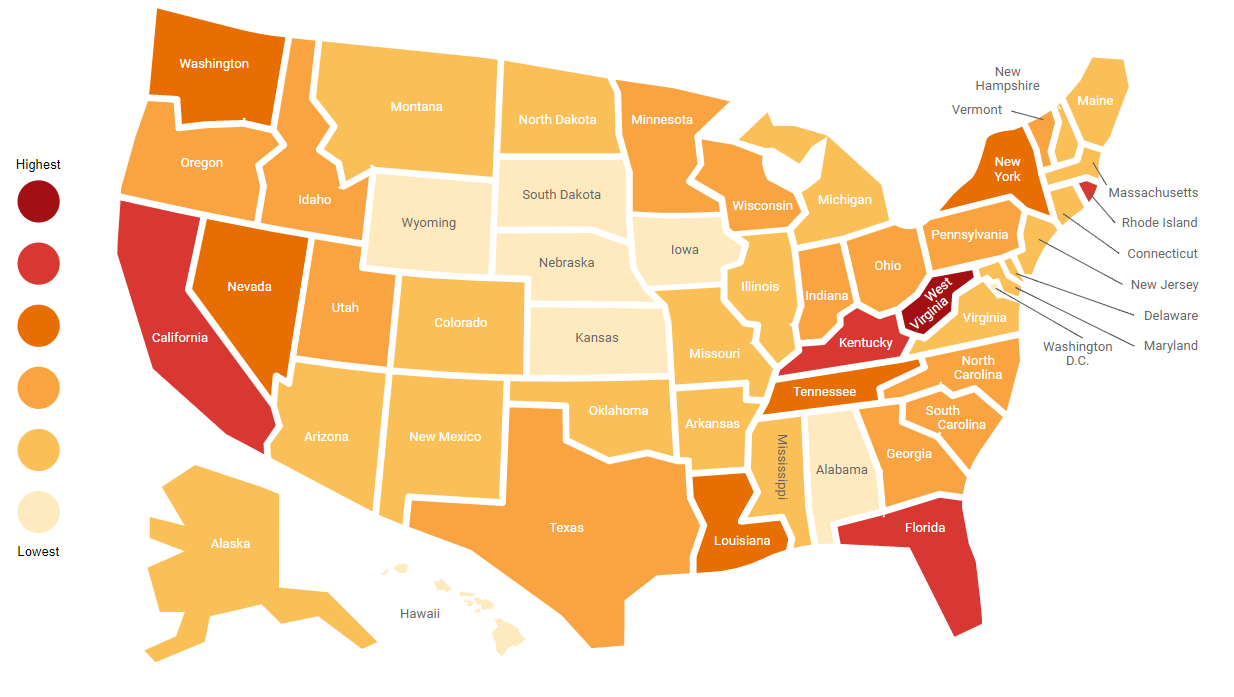

Nearly every state is affected by the opioid crisis, some more than others

The opioid crisis is a national health emergency, but some states are hit harder than others.

California, Rhode Island, West Virginia, Kentucky and Florida suffer the most from opioid abuse, according to Fair Health, a New York-based nonprofit market research firm that analyzed 26 billion privately-billed medical and dental insurance claims from 2002 until 2017.

“Using that database, the national heat map represents opioid abuse and dependence [insurance] claim lines as a percentage of total medical claim lines by state in 2017,” the researchers said. The darker colors have the higher percentages of claims.

The firm mapped out how each state was affected by opioids, as well as the medical help residents received, the total cost of those procedures, plus the age and socio-economic background of patients. West Virginia had most opioid-related claims last year, according to the report.

How does treatment for chronic pain vary by state?

• “Methadone administration was particularly associated with the Northeast, while another medication, naltrexone injection, was more closely associated with the Midwest.”

• “Outpatient rehabilitative services were linked more to the South and West than to other regions.”

• “The South relied more on testing than on therapeutic procedures, while the West had a strong emphasis on treatment.”

• “Only New York had group counseling as one of its five most common procedures by utilization and cost.”

• “Only five states—Delaware, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota and Wisconsin—included psychotherapy, 45 minutes, as one of their five most common procedures by utilization.

West Virginia had a rate of 43.4 deaths per 100,000 in 2016, up from 1.8 deaths per 100,000 in 1999, according to a separate report from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. In the U.S., opioid-related deaths rose from 1.8 per 100,000 in 1999 to 13.3 per 100,000 in 2016.

Why do some states have a higher opioid use than others?

There was a shift away from pharmaceuticals and prescriptions to illicit drugs like fentanyl and heroin between 2012 and 2014, according to a state government proposal from January responding to the opioid crisis. Officials also said more should be done to stop medical professionals from prescribing certain opioid-related pain medications and expand law enforcement-driven programs.

Figures differ on the rate of opioid use and misuse in various states, but experts say the causes relate to the rate of prescribed opioids and the public-health infrastructure in place to deal with opioid addiction. Some states had significant increases in death rates involving prescription opioids: West Virginia, Maryland, Maine, and Utah, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That, plus an influx of illegal opioids, has contributed to abuse in some areas. “Effective, synchronized programs to prevent drug overdoses will require coordination of law enforcement, first responders, mental health/substance-abuse providers, public health agencies, and community partners,” said Puja Seth, lead author of the CDC report on opioid abuse published in March.

Residents in poorer areas may be less able to afford alternative treatments for chronic pain and more prone to opioid abuse. Physicians may also have less time to spend treating patients.

Residents in states with lower household incomes may be more prone to opioid abuse. Americans on a low income may not be able to afford alternative care or surgery, which effectively means they would have more need for opioid prescriptions to deal with chronic pain. Another problem: Some people may not be able to take time off work and/or may not be able to pay to travel to clinics for regular care.

Physicians may also have less time to spend treating and diagnosing patients. Hospital systems and even health-insurance companies “gobbling up primary-care practices (PCP) has led to drive-by appointments” where PCPs need to average 7- to 8-minute appointments in order to hit productivity targets, says Dave Chase, author of “The Opioid Crisis Wake-up Call.”

Back pain, he says, is a prime example. “Even though there’s no evidence that opioids are the most effective way to address lower back pain, opioids are commonly prescribed,” Chase says.

The absence of high-quality primary-care physicians is a significant factor. “In less populated states like Kentucky and West Virginia, there is a tendency to practice more traditional pain management techniques, which may rely heavily on medications as this approach is quick, cheap and, in the short run, can be effective,” Dr. Akash Bajaj, a pain management specialist in Marina Del Rey, Calif.

“However, as we have seen this problem can quickly spiral out of control due to the need to take more medication to achieve the same effect,” he said. “We focus more on definitive therapy, identifying the problem and treating as specifically as possible, without medication management.”

‘There are some doctors who will indulge a patient’s desire for painkillers, which often take the form of opioids, in order to keep their practices afloat. This is not good for the patient or the practice.’

—Dr. Akash Bajaj, a pain management specialist in Marina Del Rey, Calif.

There is also heavy competition among physicians for patient, Bajaj says. “There are some doctors who will indulge a patient’s desire for painkillers, which often take the form of opioids, in order to keep their practices afloat,” he says. “Of course, this is not good for the patient or the practice and, thankfully, there has been a crackdown on such practices.”

But it’s easier for patients to find opioids when there are more physicians to choose from, he adds. “In more populated states like California and Florida, patients are more willing to doctor shop until they find someone willing to give them what they think they need,” Bajaj says. “This is not only a violation of ethics, but can put the patient’s life in danger.”

The dearth of appropriate treatment centers may also play a major part in the rate of deaths by state. Methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone are the three drugs used to combat the effects of opioid addiction, and treatment centers need at least three specific treatments to deal with opioid addicts, according to the journal HealthAffairs.org.

Opioid abuse is getting worse. There was an estimated 71,500 drug overdose deaths in the 12-month period ending in January, up from 67,000 predicted deaths for the previous 12-month period, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Even more deaths are being investigated. Nebraska saw the largest jump in overdoses (33%), though it was still among the least affected states according to the Fair Health study.

The crisis is estimated to cost the country more than $500 billion a year, as of 2015, according to a report from the Council of Economic Advisers. President Trump declared said he would consider bringing lawsuits against “bad actors,” including companies.

In March, the president called for more ways to combat the opioid epidemic, including instructing the Justice Department to seek more death-penalty cases against drug traffickers and asking for more federal support of overdose-reversal medications, including naloxone.