As we glide silently up Amsterdam’s busy waterways on an unseasonably warm autumn morning, boat company owner Rik Kooij, 38, admits that “canal water runs in my veins”.

Ever since his mechanically-minded grandfather renovated a bicycle, then a motorbike, then a boat back in the 1920s, Mr Kooij’s family has been at the heart of Amsterdam’s tourist canal boat business.

The Prinses Irene, which once took Winston Churchill up the canals, is silent because it’s electric. All you hear is the swoosh of the water being churned up by the propeller. And there are no acrid diesel fumes to spoil the experience.

When Mr Kooij had to take the helm of the family business following the sudden death of his father in 2013, he wasn’t daunted because he’d been working the canals since he was a boy.

Now the Reederij Kooij boat company he runs with his wife Daniela is one of the largest ploughing Amsterdam’s famous canals. It owns 32 boats out of about 150 catering to the city’s many tourists.

But when the municipality of Amsterdam stipulated that all boats would have to switch from diesel to electric power by 2025, in an effort to reduce pollution and greenhouse gas emissions, boat companies were faced with a huge – and expensive – challenge.

“We prefer to do everything that is good for the environment,” says Mr Kooij diplomatically, “but it is going to cost us millions of euros. Too much!

“But if we don’t do it we won’t get a permit to operate, so our boats will be just scrap metal.”

He has converted six boats so far – it takes about three months to strip out the old diesel engine and install the electric engine and batteries. A typical 23m (75ft) tourist boat needs about 66 batteries, he says, making the conversion cost around 165,000 to 250,000 euros ($189,000 to $287,000; £145,000 to £220,000) per boat.

But the engines are quieter, cleaner and cheaper to run – boat companies should recoup their costs in about 12 years, according to the Paris Process on Mobility and Climate, a body supporting sustainable transport projects.

They can be recharged in about 10 hours and last about two days between charges, says Sigrid Hanekamp, an application engineer from Dutch battery company Lithium Werks, which supplied the batteries for Reederij Kooij’s boats.

These batteries are not your typical lead-acid type traditionally used in cars, or even the type of lithium-ion ones becoming standard in electric vehicles, she explains. They’re lithium-iron-phosphate, a chemistry Lithium Werks believes is more durable and environmentally friendly.

They might not be as energy dense as some other types of battery, but they can be charged quickly and last longer than many other lithium-ion battery chemistries, the company says. And as they use iron rather than the much less plentiful cobalt, they’re easier to produce and less prone to price fluctuations.

But isn’t water and electricity a dangerous mix?

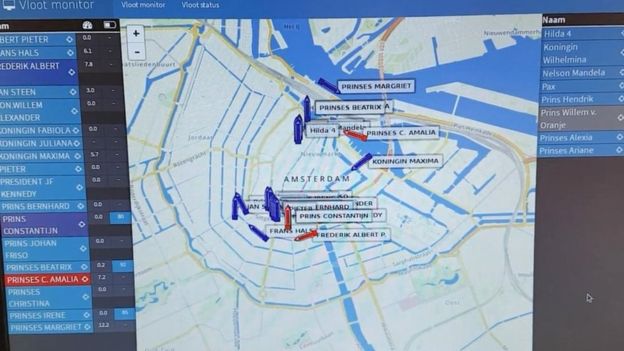

Arjan Kooijman, director of E-Ship, a firm that converts diesel boats to electric, says connected sensors on the batteries are constantly sending performance data back to the boat company’s headquarters.

Software monitors the health and charge of each battery. And if any water does get in to the insulated unit, a fuse blows, isolating it, and an alarm alerts the operator back at base.

“People used to think it was impossible to make a big ship electric 10 years ago, but we’ve shown that it can be done,” says Mr Kooijman, whose company stands to do a brisk trade over the next few years.

By 2020, Amsterdam aims to have decreased energy consumption by 20% and increased use of renewable energy by the same percentage. The electrification of canal cruise boats is a significant part of this plan.

But another challenge the boat companies face is installing enough dockside charging stations. Mr Kooij says he will have to stagger the charging rota, as it doesn’t make commercial sense to have one charging station per boat.

This is where a two-day operating range and monitoring software comes in handy. If a boat skipper drives too fast – there’s a 6km/h (4mph) speed limit on the internal canals – and drains the batteries too quickly, the software alerts headquarters, which then warns the skipper.

Amsterdam has been a pioneer in low-carbon transport for many years. Back in 2009 the Lovers boat company launched the first tourist boat powered by hydrogen cells.

The Nemo H2 uses hydrogen and oxygen to create electricity – the only by-product is water vapour.

And earlier this year, the Netherlands and Belgium announced a plan to launch zero-emissions, self-piloting container barges to sail from Amsterdam, Antwerp and Rotterdam. The barges could remove 23,000 lorries from the roads, claims Port Liner, the firm making the boats.

While retrofitting canal boats with electric engines and batteries is a time-consuming and expensive task, Amsterdam is hoping the cleaner air and waterways will attract more tourists, be better for wildlife, and contribute to carbon emission reduction targets.