Guardian investigation reveals how a small firm of wealth advisers built up a $3bn ‘golden passports’ industry and gained influence in the Caribbean

It was supposed to be a lunch, but the Swiss businessman was not eating. As his companions tucked into their pasta, Christian Kälin sipped mineral water.

The party had gathered at a restaurant overlooking the golf course in Frigate Bay, on the Caribbean island of St Kitts. Kälin, wiry and softly spoken, was in town to keep an eye on the general election in the former British colony.

The date had been set for 25 January 2010.

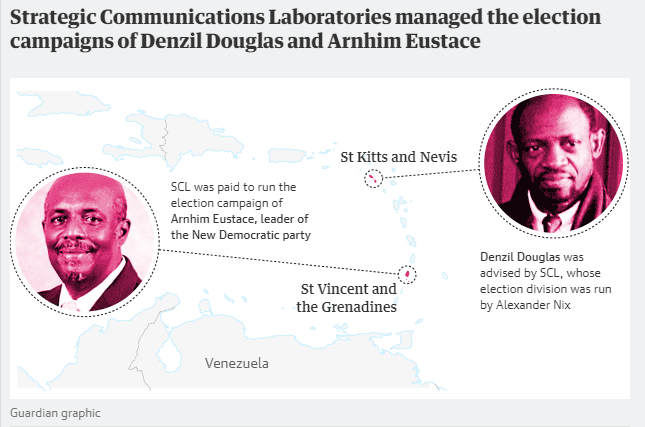

With him was Alexander Nix, the now-notorious founder of Cambridge Analytica. Back then, the bespectacled old Etonian was running the elections division of Strategic Communications Laboratories, known as SCL.

Nix was being paid to help secure a fourth term for the country’s Labour prime minister, Denzil Douglas. Kälin wanted to know if Douglas was going to win. He had been offering advice to SCL and its candidate.

In the Caribbean, they call Kälin, 46, the passport king – he has transformed a small firm of wealth advisers into the leading player in a $3bn (£2.3bn) global industry. His company, Henley & Partners, tells small countries how to transform passports into cash – a legitimate and legal business.

In exchange for donations to a national trust fund, or investments in property or government bonds, foreign nationals can become citizens of a country in which they have never lived.

Henley has made tens of millions of dollars from this trade, and its first big client was the government of St Kitts. And while Nix’s star has fallen, Kälin and his industry are on the up – and finding themselves increasingly under scrutiny.

The “golden passports” business is now a pressing concern for European governments and their intelligence agencies. For a few hundred thousand dollars, the right passport, from the right place, can get its owner into almost any country. A sum worth paying for legitimate traders.

But also, police fear, for criminals and sanctions-busting businessmen.

MPs told of ‘faustian pact’ to sway elections

In July, this business, and its roots, was also a concern for British MPs. Members of the digital, culture, media and sport select committee had begun to look at the issue of “fake news”, but they soon found themselves at the centre of one of the issues of the age: the tactics, fair and foul, that can be used to sway elections, and potentially undermine democracy.

The testimony heard by MPs laid bare the disreputable behaviour of Cambridge Analytica, and its sister company, SCL. In a small section of an 89-page interim report, they described being told there was a “faustian pact” between Nix and Kälin. A pact created, they were told, to influence the outcome of elections in places where Henley wanted to do business.

Behind a number of SCL’s Caribbean campaigns was the “hidden hand” of Henley, which “arranged for investors to supply the funding for the campaigns”, the report claimed. “In exchange,” MPs alleged, “Henley & Partners would gain exclusive passport rights for that country.”

It was quite an accusation. One that Kälin insists is completely untrue.

There was no pact, he says, no hidden hand, no payments, no commercial arrangements – and certainly no wrongdoing. “You have the right story,” Kälin told the Guardian. “But you are talking to the wrong people.”

For the past five months, the Guardian has been investigating the evolution of this global business – to try to establish what went on between the two men and the two companies back then, and whether this has any bearing on what is happening now.

Details from hundreds of emails and internal SCL documents, supported by interviews with key players, have shed new light on their relationship, and the problems that come from a lack of transparency.

The findings certainly raise questions about the conduct of elections in the Caribbean. And they reveal the considerable influence exerted by Kälin in the region.

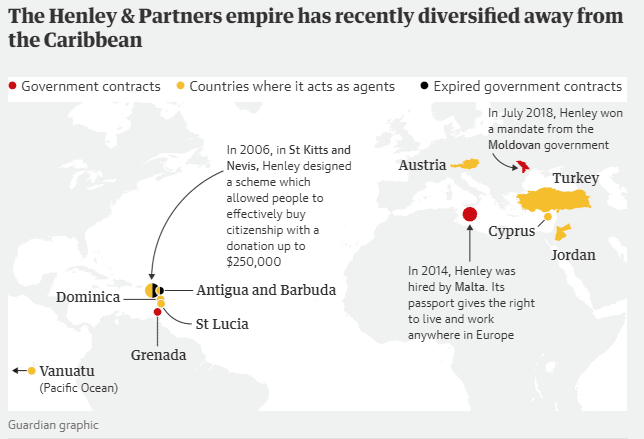

Henley’s success story began in 2006, when it was hired on a five-year contract to relaunch the St Kitts citizenship by investment scheme. For every successful application, the firm would collect $20,000. As of today, St Kitts has sold more than 16,000 passports for as much as $250,000 each.

The money was a godsend, coming just after the collapse of sugar exports, a trade that had kept the country afloat after independence. Caribbean passports are valuable because they allow visa-free travel to 130 countries including the UK and many European states – a prize for wealthy elites from Russia, China and the Middle East.

When St Kitts signed the accord that removed travel restrictions to Europe in 2009, the number of passport buyers doubled in a year.

When British MPs looked into SCL, one of the things they wanted know was who had funded its work on Caribbean elections.

Nix seemed to point a finger. He told the committee: “My understanding is that he [Kälin] may well have financed some of the elections or given contributions towards some of the elections” SCL had worked on.

The St Kitts Labour party has now come forward. A well-placed source, who spoke on condition of anonymity, was adamant the party itself had not paid a penny to SCL. The source assumed Henley was using its connections to find people willing to stump up.

“Henley was identifying and approaching persons willing to make donations for the campaign,” the source alleged.

“The Labour party were never told who these people were. All we knew was SCL was going to manage the campaign and Kälin’s role was to facilitate the payment. We never really got into who was making the contributions.”

In November 2009, sources claim, Nix emailed an estimate for its work on the forthcoming election to Douglas. The sum was about $2.7m, and the message was apparently copied to Kälin, though he cannot recall receiving it.

So was Henley facilitating payments and arranging for the bills to be paid? Kälin denies it. “This is rubbish. This whole notion that we raised or organised the financing is misguided,” he said.

Kälin insisted there was no coordinated effort by him, or Henley, to raise money for SCL. But he admitted many of his wealthy clients could have donated to the campaign.

He recalled meetings where he introduced people to Douglas and SCL, which, he said, he saw as part of his mandate as the then honorary consul for St Kitts in Switzerland.

“At that time I had direct interaction with clients. They trusted me. The prime minister trusted me. So I introduced many people to the prime minister. For sure many of them would have gone on to make a donation.”

Some of those donations, he says, would have been paid directly to SCL, but not all donors were Henley clients.

How SCL managed the election campaigns of Denzil Douglas and Arnhim Eustace

Kälin says he had nothing to gain by supporting Labour because the passport contract, which was with the government not a political party, had a clause granting Henley another five years if it met certain conditions.

They were met, says Kälin, and the contract was extended in mid-2011. Two years later, however, Henley and the government scrapped the deal early, by mutual consent.

“If we influenced the election in order to get something in return, our contract would have been renewed without question,” Kälin said.

So claims made to MPs about a ”faustian pact” between Henley and SCL show, he says, he is the victim of politically and commercially motivated attacks.

Kälin is also sensitive about his firm’s relationship with SCL. He insists there was “no formal relationship” between them; they only communicated because they were in the same place at the same time, advising the same clients.

The documents reviewed by the Guardian confirm there was extensive cooperation between SCL and Henley.

After securing Douglas’s re-election in 2010, SCL shifted focus to the St Vincent and Grenadines general election. During this campaign, the files show Kälin was communicating with SCL staff on a sometimes daily basis.

They suggest the Swiss businessman was closely involved in strategy and at times issued direct advice to SCL staff, who were working to secure the election of the opposition leader, Arnhim Eustace.

Kälin admits he was a fan of Eustace, a former finance minister who had embraced the idea of setting up a citizenship scheme of the kind Henley was pioneering. But he maintains Henley did not work on SCL’s election campaign.

“Of course we had an interest in the outcome, in the larger sense,” Kälin said in an interview at Henley’s London office. “There’s nothing wrong with that.”

But he says there was no prior agreement to grant Henley a contract, or any other special treatment, if Eustace won. Indeed, the intention to set up a passports scheme was not even mentioned in the candidate’s manifesto.

‘This is what we could do for you in government’

Even today, this election is remembered as one of the dirtiest ever held in the comparatively young democracies of the eastern Caribbean. “Election campaigns here sank to a new low,” recalls Jude Knight, of Searchlight, a local newspaper. “Stuff we have never experienced in this region before.”

Aggressive tactics on both sides left even SCL staff afraid for their safety. Plans for an emergency evacuation were made, which could be triggered by sending a text with the word NODUFF.

SCL’s work on the campaign did not come cheap. Among the files is what appears to be an estimate for the campaign. Dated April, 2010, the price quoted is just under $5m – for an electorate of 80,000 voters. Another document is a presentation on SCL’s strategy, entitled “financier presso”.

The Guardian has been told by a former employee it was written for Kälin, and delivered via a Skype video call. A spreadsheet, setting out SCL’s spending was one of many prepared for Kälin, a second SCL source claimed.

But none of the documents seen by the Guardian states who actually paid the bills. Kälin denies it was him but admits he was more involved in the politics of the campaign than he should have been.

Four days before polls opened, Eustace held his closing rally in Victoria Park in Kingstown. In his hand he held the party’s manifesto. It claimed his New Democratic party (NDP) had held “discussions with several interested investors” from outside the country who were committed to spend millions of dollars on a number of new projects if they won; among them, a holiday resort, a chain of retail banks and a regional head office for a construction group.

Eustace did not name the would-be investors. The correspondence suggests he never knew their names. But Kälin must have done.

Days before the rally, he had emailed Eustace. “This is what we could do for you once you are in government,” he wrote. “Please feel free to use any of the above points in your manifesto, campaign messages etc. as all of this I can personally assure you we will be able to actually realise.”

Despite all their efforts, Eustace lost the election on 13 December 2010. But it was a result Kälin appeared unwilling to accept. The files suggest he was among those urging the NDP to launch a legal challenge. The NDP had lost by a single seat, and many felt there were grounds for concern.

The day after the election, SCL wrote a speech for Eustace; it was sent to Kälin, then requested it to be sent to the candidate, with the following message.

“Please just review it with your lawyer briefly, make no or as little changes as possible, and then address this to the nation. It fits in a larger scheme of things which we are designing to achieve the desired results.”

Eustace, who made the speech, said it was not unusual for SCL to do the drafts. In the event, his challenge petered out. SCL believed he was tired of being bossed around, according to a “debrief” document circulated to senior staff – and to Kälin.

That description did not go down well with Eustace. In a statement to the Guardian, he said it was “frankly patronising” to think SCL or Henley was in charge of his campaign, though he said Kälin may have given his opinion.

As to how the campaign was financed, he says international donors “were introduced by Henley & Partners”, and that “some of our donors’ contributions were paid directly to SCL”.

Kälin denies issuing instructions to SCL, or to Eustace. He agrees clients of his may well have given money to SCL in St Vincent, but insists he was not the facilitator. He does concede, however, it was a misjudgment to have got involved in the political process.

“In hindsight I would say yes, we probably would be better off not to get too closely involved in that because it looks not so good. Like we now realise.” He added: “Maybe there is a certain naivety, I would agree, because although I had a lot of experience in the Caribbean, I had zero experience with political campaigns.”

Naive or not, the fact remains that nobody seems to know, or is prepared to say, who paid for SCL’s services in St Kitts and St Vincent. Nix won’t say. Kälin says it wasn’t him.

The question is important, because SCL’s costs represented the majority of spending in both campaigns. Its work included advertising on TV, radio and billboards, chartering flights for voters from the Caribbean diaspora, and organising lavish rallies with fireworks and musicians.

Neither state has campaign finance laws obliging political parties to name donors, or be transparent on campaign spending. Regional bodies including the Organisation of American States have urged better disclosure, saying the sums spent on elections are rising, but citizens lack information.

No wonder, then, that the US and British governments, among others, have expressed concerns about the “passports for cash” programmes that have been set up across the Caribbean.

For Fyard Hosein, there are questions that need answering. An eminent QC from Trinidad and Tobago, he was recruited by Kälin to monitor the St Vincent voting on election night.

Hosein has not spoken before, but he says the revelations about Cambridge Analytica have prompted him to set out his concerns.

After Eustace was defeated, Hosein says he had lunch with Kälin. “He asked me to send a bill and I never sent a bill. So far as I was concerned I was doing a public service.”

But he is still troubled by that election, the role played by SCL and the opaqueness of the funding for campaigns. “I have a real, deep desire to ensure there is some kind of clarity about election intervention by foreign agents.”

In July, Henley won a contract with the Moldovan government, and before that, it was appointed to manage a programme for Grenada. Last year, it opened an office in St Lucia.

But its prize client since 2014 has been the government of Malta. Its passport is particularly valuable because it bestows the right to live and work anywhere in Europe.

Eight years after the lunch in Frigate Bay, SCL may have hit the rocks, but Kälin’s ship is still very much afloat.