It was quiet out there in the markets—spooky quiet. All five of the calmest quarters for U.S. stocks in the past 20 years have occurred since the start of 2017. Then came Oct. 10-11, when markets were hit by a storm that came out of the clear blue sky. The S&P 500 fell 5.2 percent over two days. That represented the fifth-biggest increase in volatility in the almost 90-year history of the index and its predecessors, according to Rocky Fishman, a Goldman Sachs Group Inc. equity derivatives strategist.

Stocks partially rebounded in the following sessions. Even so, there was a sense that something had changed. Several of the previous volatility spikes had clear causes, such as the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, President Dwight Eisenhower’s heart attack in 1955, and the failure of a United Airlines buyout in 1989. This time around, Democrats quickly blamed the minicrash on President Trump’s trade policies, while other observers cited higher oil prices, the strong dollar, or rising labor costs. The president blamed the Federal Reserve, which he says will damage economic growth by raising interest rates too much. “I think the Fed is making a mistake,” he said on Oct. 10. “They’re so tight. I think the Fed has gone crazy.”

Trump isn’t entirely wrong. Many economists and market strategists agree with him that higher interest rates are a big factor in the stock market’s sudden weakness. Where they part company with the man in the White House is over Trump’s conviction that the Fed is making a mistake. Many say a gradual course of rising rates is just what the economy needs now—even if that makes stock investors nervous.

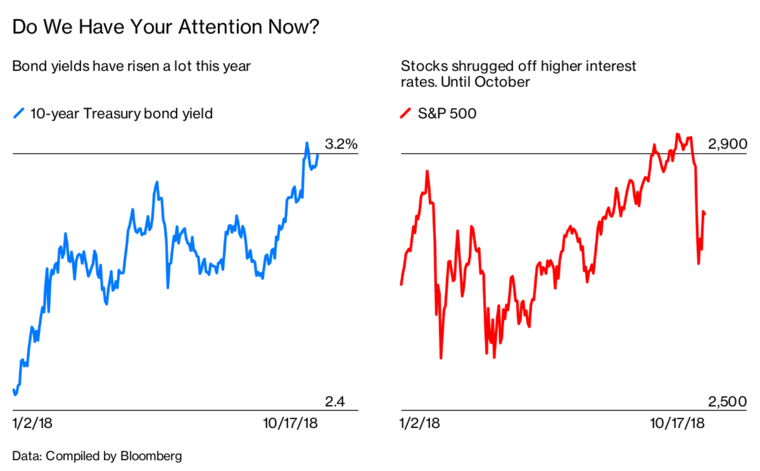

“This is not a level of interest rates that should be destabilizing,” says Michelle Meyer, head of U.S. economics for Bank of America Merrill Lynch. It’s the speed of the rise in longer-term rates that seems to have spooked stock investors, she says. The yield on 10-year Treasury notes jumped from 2.4 percent at the start of 2018 to more than 3.2 percent in early October, right before stocks tumbled.

Investors far from Wall Street are puzzled about the stock market right now. “There’s part of me that would be relieved if it dropped 20 to 25 percent,” says Jon Anderson, 64, of Duluth, Minn., who works at a software consulting firm and has 55 percent of his savings in stocks. “I think the market is way overpriced.” Karen Kamenir, a part-time bus driver in Mesa, Ariz., who used to sell houses, says the week of the minicrash she bought some certificates of deposit to diversify her stock-heavy portfolio: “It was taking a little bit of risk off the table.”

That caution is new. In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, stock investors got used to the idea that they had little to fear from rising interest rates. The Fed raises rates to combat inflation, and with the economy still in recovery mode, there was little sign of rising consumer prices. When inflation and rates did begin to creep up, it was mainly viewed as evidence that the economy was finally growing again, increasing corporate profits. Rates were still low by historical standards—too low to chill borrowing and growth. That’s one reason stocks have been in a long, strong bull market since their nadir in March 2009. Higher rates and higher stock prices both reflected optimism about the economy.

The relationship between stock prices and interest rates is complicated and changeable, though. In the long run, bonds and stocks are competing investments. Now that investors can earn more than 3 percent by buying safe Treasuries, stocks look less compelling, especially because valuations have been swollen by the bull market. The ratio of stock prices to earnings per share of companies in the S&P 500 is 20, above its long-run average of 17. Investors are paying a lot for the profits of the companies they own.

For market professionals, the most significant thing that happened in early October was a flip in investor psychology. The correlation between stock prices and interest rates, as measured over the prior 52 weeks, turned from positive to negative—so higher rates implied lower stock prices. That’s happened only four times since 1989, and it’s a bad signal for stocks, says James Paulsen, chief investment strategist for Leuthold Group in Minneapolis. Two of the four times were followed by a bear market in stocks, and one was followed by a pair of back-to-back smaller declines, he says.

Paulsen agrees with Meyer that interest rates aren’t chokingly high. But, he says, “it’s not about the rate level. What’s important is when the mindset of Wall Street changes.” Evidence that inflation is finally picking up may explain Wall Street’s new thinking, says Liz Ann Sonders, chief investment strategist at Charles Schwab & Co. Now that inflation has reached the Fed’s 2 percent target, even stock investors who were previously focused on improved earnings begin to worry about consumer price increases. They fear the Fed will react to high inflation by jacking up rates faster. Says Gina Martin Adams, chief equity strategist for Bloomberg Intelligence: “There’s something pretty fundamental that’s started to weigh on the outlook for stocks, and it seems to be related to inflation.”

Some strategists are confident the bull market will endure even if rates continue to rise. They reason that the Fed under Chairman Jerome Powell won’t make the mistake of raising rates too fast and snuffing out the expansion. Brian Belski, chief investment strategist at BMO Capital Markets, and Nicholas Roccanova, a senior investment strategist, wrote in an Oct. 11 note that “periods of higher or rising rates have coincided with double-digit annual returns for the S&P 500, on average.” That may be. But if Oct. 10-11 taught us anything, it’s that bad weather can escape the radar’s notice, and hibernating bears can suddenly emerge from their caves.