Countries around the world are pushing back against China’s revival as a major global power.

China’s sheer size and population make it a heavyweight, and a clear strategic rival to the United States. It is the world’s most populous country and among its largest.

Its influence has boomed – along with its economy – in recent years, as the US and Europe nursed the wounds from devastating financial crises.

This has concerned several countries, particularly the US, which is keen to retain its dominant position in the world.

Here are some areas where governments are grappling with Chinese influence.

Trade war… and beyond?

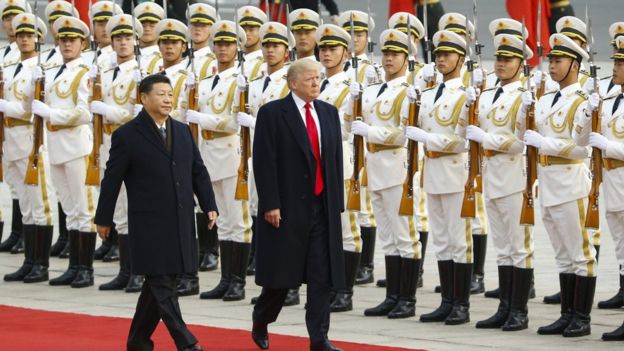

US President Donald Trump’s administration launched a trade war with China this year, hitting about half of Chinese imports to the US with tariffs.

It says the tariffs are a response to China’s “unfair” trade practices and alleged intellectual property theft.

They are part of a protectionist policy which has seen the Trump administration pull out of and renegotiate multilateral trade deals and challenge the global free trade system.

Many in Beijing suspect that the US wants to block China’s rise – which is seen as a challenge to the US’s own established hegemony.

Speaking at the World Economic Forum in Davos in 2017, Chinese President Xi Jinping said: “Countries have the right to development, but they should view their own interests in the broader context. And refrain from pursuing their own interests at the expense of others.”

Yet since the opening salvo, the dispute between the world’s two largest economies has not only escalated but also broadened.

In a recent speech, US Vice President Mike Pence said China had chosen “economic aggression” when engaging with the world and “debt diplomacy” to spread its influence. There was “no doubt” China was meddling in America’s democracy, he said.

The scale and multitude of attacks has many analysts thinking the US-China dispute is about more than just trade.

“The Chinese think the US wants to contain them and certainly a lot of people here do. A lot of people in the US think the Chinese want to take over the world,” said C. Fred Bergsten, founding director of the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington.

“All current Americans grew up in a world where the US is dominant… when somebody seriously challenges that, as the Chinese are, it’s viewed as a pretty fundamental threat and risk.”

While the pressure on the US government for a more assertive policy towards China has grown over the years, some say Mr Trump is carrying out an “extreme” and “crude” version it.

Meanwhile, Chinese President Xi Jinping’s greater claims on power are making many nervous.

“The big egos and strong stances of the two leaders are exacerbating it so at the moment it’s really a collision course towards a cold war,” said Mr Bergsten, who previously also worked as former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger’s deputy for economic policy.

National security

Australia’s parliament this year passed new laws to prevent foreign interference in the country, which was widely seen as targeting China.

China’s growing influence is a concern in New Zealand too, where a Chinese-born MP last year denied allegations he was a Chinese spy.

National security worries have also led to curbs on Chinese companies, such as telecoms giant Huawei and ZTE, and on Chinese investment abroad.

The Australian government banned Huawei and ZTE from providing 5G technology for the country’s wireless networks, while a UK security committee has expressed some concern about Huawei’s telecoms kit.

“I think there is a genuine reason to be concerned because of the lack of transparency about Huawei’s relationship with the Chinese government and the Communist Party,” said Steve Tsang, director of SOAS China Institute in London.

Germany’s government earlier this year also vetoed the takeover of an engineering company by a Chinese firm on the grounds of national security.

‘Debt diplomacy’

Countries that are supposed to be benefiting from China’s increased wealth also seem to be growing more cautious.

Beijing’s Belt And Road initiative, first unveiled in 2013, aims to expand trade links between Asia, Africa, Europe and beyond.

But the multi-billion dollar project, which some fear could cause debt problems in certain countries, is facing growing resistance.

Sri Lanka, Malaysia and Pakistan have all expressed concerns about the programme. Recipient countries worry about debt accumulation and increased Chinese influence at home.

“I think first and foremost this is a tool for China to expand, to strengthen its soft power influence through economic diplomacy,” said Michael Hirson, Asia director at Eurasia Group.

“There is also a strong strategic dimension which comes into play in the projects that focus on the energy sector and on port deals which serve China’s interest in securing strategic assets overseas.”

Mr Pence highlighted these strategic interests in his speech flagging the experience of Sri Lanka, which had to hand over the control of a port to China to help repay foreign loans.

“China uses so-called ‘debt diplomacy’ to expand its influence. Today, that country is offering hundreds of billions of dollars in infrastructure loans to governments from Asia to Africa to Europe and even Latin America,” Mr Pence said.

“Yet the terms of those loans are opaque at best, and the benefits invariably flow overwhelmingly to Beijing. Just ask Sri Lanka.”