Major United Nations agencies are urging key fishing nations to join efforts to fight illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing.

BANGKOK — Major United Nations agencies are urging key fishing nations to join efforts to fight illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing.

The U.N. Food and Agricultural Organization and other groups made the call at a conference in Bangkok on Wednesday focused on helping protect fisheries and those working in the industry.

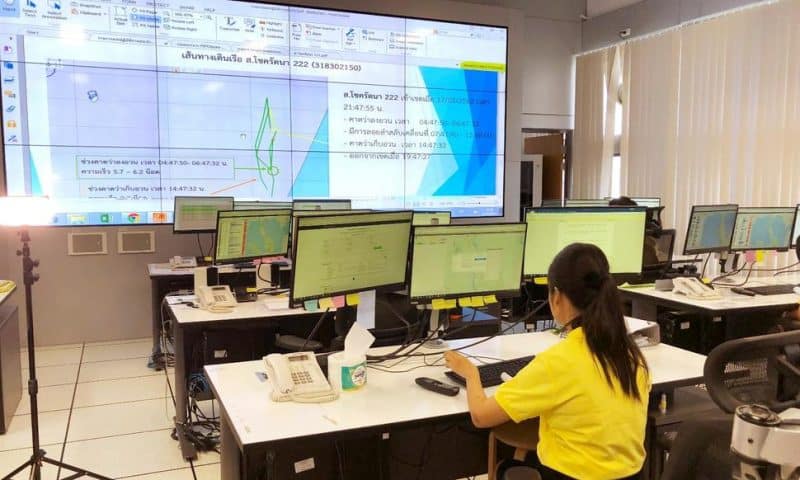

Thailand is the world’s biggest importer of tuna. It has one of the seven state-of-the-art centers in the region monitoring fishing vessels in real time to help control access to regional ports and curb illegal fishing.

The centers are helping enforce the Port State Measures Agreement, which aims to help curb illegal, unreported and unregulated — or IUU — fishing. Dozens of governments have joined but U.N. officials are urging more to support the effort.

Illegal fishing costs countries in the Asia-Pacific region some $5 billion a year; globally more than $20 billion. And rogue fishing vessels often engage in other crimes such as piracy and human and drug trafficking, abuses being fought along with the International Labor Organization and International Organization for Migration.

Preventing such vessels from selling illegal catches is the most vital element for stopping illegal fishing, Adisorn Promthep, director-general of Thailand’s Department of Fisheries, said during a visit to the center in Bangkok.

“We also make certain that no IUU fish or products come to Thailand and this is going to be a big help to work against IUU,” Adisorn said in an interview.

A Pulitzer Prize-winning Associated Press investigation in 2015-16 that uncovered severe rights abuses affecting migrant workers in Thailand’s fishing and seafood industries helped focus attention on the problem. The stories helped free more than 2,000 enslaved men from Myanmar, Cambodia, Thailand and Laos, and led to more than a dozen arrests, amended U.S. laws and lawsuits seeking redress.

The European Union in 2015 gave Thailand a “yellow card” on its fishing exports, warning that it could face a ban on EU sales if it didn’t reform the industry. Thailand’s then-military government responded by introducing new regulations and setting up the command center to fight illegal fishing.

During a recent visit, about a dozen staff in the surveillance center were keeping a round-the-clock watch on the positions of fishing and other vessels to see if they were operating in areas they were not authorized to fish in.

The system includes detailed online records and photographs of each vessel, their crews, logs and other information that is verified by officials at ports before the ships are allowed to unload catches, refuel or restock.

The FAO estimates that almost a third of global fish stocks are degraded from overfishing, and a further 60% are “fully exploited.” Illegal catches account for much of the overfishing, or up to 26 million tons a year, at times nearly one-fifth of the total harvest from the sea.

And while the systems are improving and expanding, they are not failsafe. In some cases, small-scale fishers are unfamiliar with territorial limits in traditional fishing areas, said Simon J. Nicol, a senior fishery official at the FAO’s Bangkok office.

Adisorn agreed that relatively recently established boundaries and controls can be a problem for some fishermen, especially artisanal, small boats. But having fishing vessels comply means a “level playing field,” he said.

Ultimately, Nicol said, the aim is not just to combat illegal fishing, but to try to ensure sustainable use of fisheries at a time of declining stocks of some species, such as the bluefin tuna favored by sushi bars.

“We are on the right track,” Nichol said.