A rising tide of nationalism in India is driving ordinary citizens to spread fake news, according to BBC research.

The research found that facts were less important to some than the emotional desire to bolster national identity.

Social media analysis suggested that right-wing networks are much more organised than on the left, pushing nationalistic fake stories further.

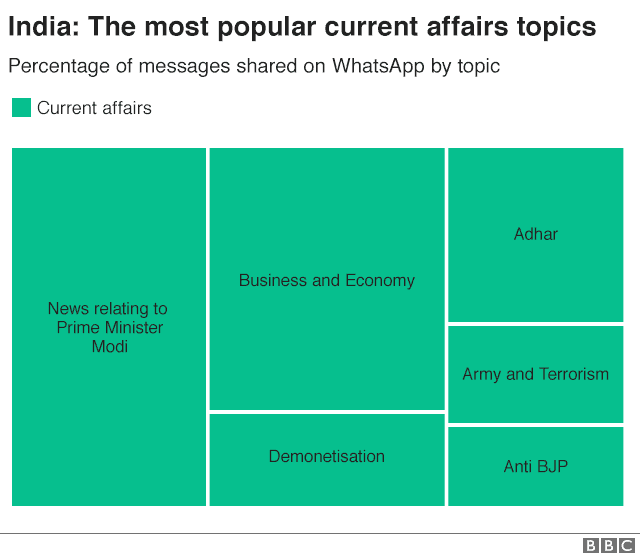

There was also an overlap of fake news sources on Twitter and support networks of Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

The findings come from extensive research in India, Kenya, and Nigeria into the way ordinary citizens engage with and spread fake news.

Participants gave the BBC extensive access to their phones over a seven-day period, allowing the researchers to examine the kinds of material they shared, whom they shared it with and how often.

The research, commissioned by the BBC World Service and published today, forms part of “Beyond Fake News” – a series across TV, radio and digital that aims to investigate how disinformation and fake news are affecting people around the world.

In all three countries, distrust of mainstream news outlets pushed people to spread information from alternative sources, without attempting to verify it, in the belief that they were helping to spread the real story. People were also overly confident in their ability to spot fake news.

The sheer flood of digital information being spread in 2018 is worsening the problem. Participants in the BBC research made little attempt to query the original source of fake news messages, looking instead to alternative signs that the information was reliable.

These included the number of comments on a Facebook post, the kinds of images on the posts, or the sender, with people assuming WhatsApp messages from family and friends could be trusted and sent on without checking.

Widespread sharing of false rumours on WhatsApp has led to a wave of violence in India, with people forwarding on fake messages about child abductors to friends and family out of a sense of duty to protect loved ones and communities.

According to a separate BBC analysis, at least 32 people have been killed in the past year in incidents involving rumours spread on social media or messaging apps.

We examined one case in detail – the deaths of Nilotpal and Abhishek in Assam – while another reporter travelled to Mexico to see how WhatsApp rumours fuelled similar deadly violence there.

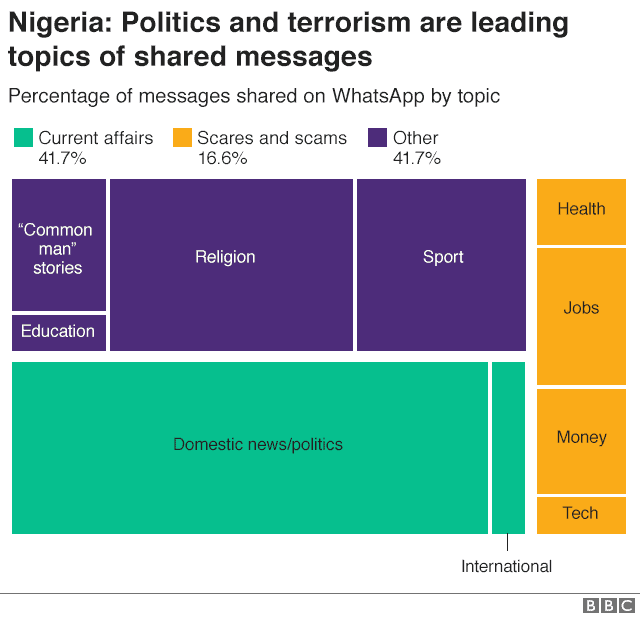

The research in Africa suggested that national identity was insignificant in the spread of fake news.

In Kenya, scams related to money and technology were a stronger driving force, contributing to around a third of stories shared on WhatsApp, while fake stories relating to terrorism and the army were widely shared in Nigeria.

In both countries, health scares were prominent among widely shared fake news stories, and many news consumers visited both credible and fake news sources without distinguishing between them.

Researchers spent hundreds of hours with 80 participants across the three countries, interviewing them at home about their media consumption as well as examining how they shared information via WhatsApp and Facebook during a seven-day period.

They also conducted extensive analysis of how fake news spreads on Twitter and Facebook in India, to understand whether the spread of fake news was politically polarised.

About 16,000 Twitter accounts and 3,000 Facebook pages were analysed. The results showed a strong and coherent promotion of right-wing messages, while left-wing fake news networks were loosely organised, if at all, and less effective.

The methodology

We set out with this research to try to answer the question of why ordinary citizens spread fake news – a little-understood part of the fake news equation.

When a phenomenon is new or not very well understood, qualitative research techniques are useful. These techniques – in this case, in-depth interviews and up-close observation of sharing behaviours – allowed us to explore fake news with nuance, richness and depth.

Because we wanted to know what was spreading in encrypted private networks such as WhatsApp, ethnographic approaches – visiting people at home – were essential.

This is the first known research project in these countries that uses these methods to understand the fake news phenomenon at the level of ordinary citizens.

It is also the first to use data science and network analysis techniques to understand how known sources of fake news are organised on Twitter and Facebook, and what their connections are with audiences.