Therapies that entail removing immune cells from patients and engineering them to recognize and fight cancer have revolutionized the treatment of some blood cancers, but they’ve proven difficult to translate to other tumor types. Researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center believe they’ve hit upon a combination treatment that could help expand the use of cell therapy.

The team combined infusions of cancer-killing T cells with Nektar Therapeutics’ experimental immunotherapy drug bempegaldesleukin (also called NKTR-214) in mouse models of melanoma. The combo produced an increased number of T cells, and those cells lived longer and functioned better than did T cells that were expanded with the protein interleukin-2. They reported the results in the journal Nature Communications.

Interleukin-2 is commonly given to patients receiving cell therapies because the protein promotes the expansion of the cells. Problem is, interleukin-2 can simultaneously activate cells that suppress the immune system, and it can cause dangerous side effects. So the UCLA team wanted to see whether a different immunotherapy drug might be able to stimulate T-cell expansion without the adverse effects.

Bempegaldesleukin, which is in a class known as CD122-preferential IL-2 pathway agonists, is a form of interleukin-2 that’s designed to quickly activate the proliferation of cancer-killing T cells and natural killer cells without over-stimulating the immune system. It is currently in clinical trials in combination with Bristol-Myers Squibb’s anti-PD-1 drug Opdivo in melanoma.

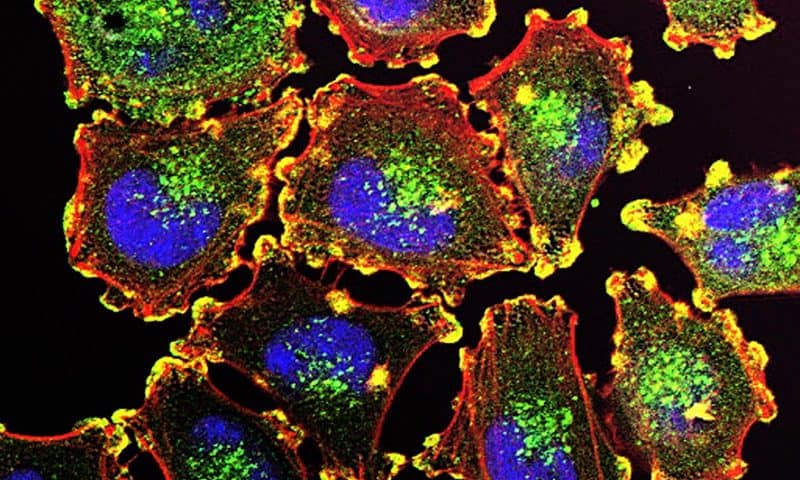

After the UCLA researchers infused T cells along with bempegaldesleukin in mice, they used bioluminescence imaging technology to track the cells as they moved through the body. They observed that the T cells expanded in the spleen, which helped accelerate their activation and expansion. The cells then moved to the tumor, where they had a long-lasting anti-cancer effect, the researchers reported. The animals that received the Nektar drug survived for up to two months longer than did those that got interleukin-2 instead.

Nektar’s investors have high hopes for NKTR-214, which has recently taken a turn for the better after initially charting mixed results in clinical trials. Top-line data from a phase 1/2 trial in of bempegaldesleukin plus Opdivo presented in 2018 were disappointing. But late last year, Nektar presented 18-month data of the combo in first-line melanoma showing durable responses in 16 out of 20 patients. The combo is now being tested in phase 3 trials in melanoma, renal cell carcinoma and muscle-invasive bladder cancer.

Several academic groups are investigating other ideas for improving T-cell therapies. Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) researchers, for example, have developed a vaccine that stimulates CAR-T cells in lymph nodes, helping to boost expansion of the cells. And MIT spinoff Torque Therapeutics is attaching nanoparticles filled with immune-stimulating drugs to T cells in the hopes of improving their ability to target cancer while leaving healthy tissue alone.

The UCLA team is planning future studies to better understand how signaling pathways contribute to the anti-cancer effects they observed in mice given the T-cell combination therapy, they wrote in the study. The synergy they’ve seen so far, they said, “suggests that in patients with cancer, NKTR-214-containing regimens could increase tumor control without exacerbating systemic inflammation.”