One popular theory in the quest to develop cures for Alzheimer’s disease is that targeting the toxic clumps of the protein beta-amyloid in the brain that are a hallmark of the disease could ameliorate symptoms. One such anti-amyloid drug, Biogen and Eisai’s aducanumab, has shown mixed efficacy in slowing cognitive decline in two clinical trials, while several similar candidates have simply failed to register any benefit, leaving many doubtful about the strategy.

Now, a research team led by scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis has proposed a possible explanation for the disappointing clinical outcomes. In a new study published in Nature, backed by findings in mice, the researchers pointed to the brain’s newly discovered drainage system, called the meningeal lymphatic system. The researchers suggested that drugs could be developed to enhance its function to improve the efficacy of treatments like aducanumab in Alzheimer’s.

PureTech Health, which holds an exclusive license to the underlying intellectual property, is now developing novel therapeutics to modulate lymphatic flow in the central nervous system. The company hopes to target a range of neurodegenerative diseases.

“The lymphatics are a sink,” Jonathan Kipnis, Ph.D., a co-author of the study, explained in a statement. “Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s and frontotemporal dementia are characterized by protein aggregation in the brain. If you break up these aggregates but you have no way to get rid of the debris because your sink is clogged, you didn’t accomplish much. You have to unclog the sink to really solve the problem.”

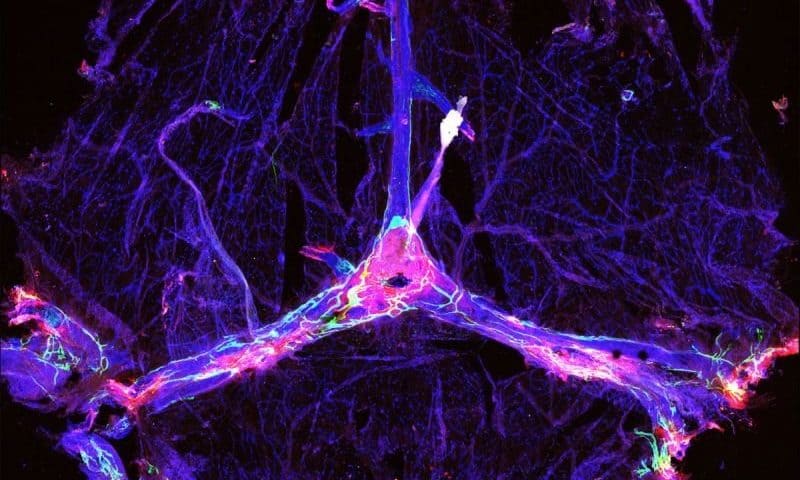

In 2015, a team led by Kipnis discovered the lymphatic system in the brains of mice. Then in 2018, he led a study that showed that ablating the meningeal lymphatic system increased beta-amyloid deposits in mice. So he hypothesized that the disappointing performance of anti-amyloid drugs may be explained by functional differences in the lymphatic drainage system in individual patients.

To test the theory, Kipnis and colleagues used versions of aducanumab and another amyloid-targeting drug BAN2401 in a mouse model of early Alzheimer’s that’s also characterized by beta-amyloid buildup. The idea was to test whether improving function of the lymphatic drainage could impact the effectiveness of the drugs.

Mice with ablated meningeal lymphatics showed significantly higher buildup of beta-amyloid plaque than did controls with intact drainage systems, the scientists found. Mice with impaired lymphatic drainage also showed decreased influx into the brain of the antibody drugs from the surrounding fluid, suggesting reduced targeting of the plaques, the team noted.

The researchers also observed changes in a type of immune cell in the brain called microglia, which work as scavengers that remove dying cells and other debris. Crippling lymphatic drainage shifted microglia to an inflammatory state, which could contribute to neurodegeneration, the researchers suggested.

What’s more, genes related to antigen processing and presentation and T-cell activity were turned down in the microglia of mice with damaged lymphatic systems, the team found. This could potentially impair the efficacy of passive immunotherapies such as amyloid-targeting antibodies, they said.

Overall, the gene-expression patterns in microglia from mice with damaged lymphatics resembled those from people with Alzheimer’s, the team showed.

To explore the therapeutic potential of meningeal lymphatics, the scientists combined aducanumab or BAN2401 with a virus-mediated vascular endothelial growth factor-C, in the hopes of expanding the network of meningeal lymphatic vessels. Mice that got the combos showed significantly decreased beta-amyloid accumulation as compared to those that were given the anti-amyloid drugs alone, according to the team.

The findings suggest it might be possible to develop drugs that target microglia and the brain blood vessels—both of which are important in Alzheimer’s—by modulating the function of the lymphatic vessels, the researchers wrote in the study. Future studies could examine the genetic signatures in humans to infer information about the integrity of the brain’s lymphatic system, so personalized combination treatments to slow the progression of Alzheimer’s can be developed, they suggested.