A cell has to know what it is to do its job. New research from Trinity College Dublin has helped reveal just how cells establish their identities, which could have implications for developing more targeted cancer treatments.

Professor Adrian Bracken and his team had been perplexed by a “puzzle” involving Polycomb protein complexes, specifically PRC1 and PRC2. These proteins are “strict librarians” inside cells, blocking access to certain areas of the genetic library—so a neuron cell can’t access a muscle gene, confusing its cellular identity, for instance, Ph.D. student Ellen Tuck, who works in the Bracken lab, said in a press release.

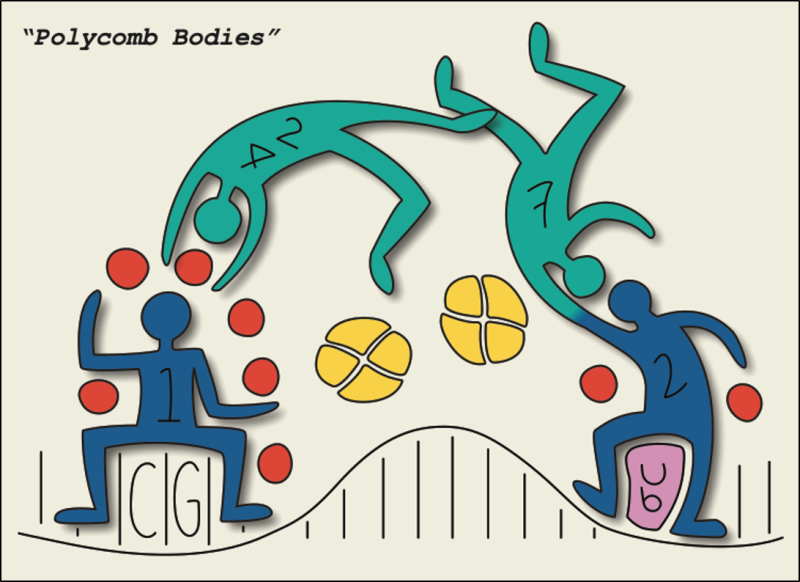

But the researchers were puzzled for two years over the fact that two forms of the PRC2 protein exist in the cell, called PRC2.1 and PRC2.2. The Bracken lab had previously shown that these two forms do the exact same thing and target the same regions of DNA but couldn’t figure out why we need two copies.

Until now. The lab’s latest work shows that the two forms of PRC2 recruit different forms of the PRC1 complex to DNA.

“This took us by complete surprise,” said Eleanor Glancy, a Ph.D. graduate from the Bracken lab. “We initially thought there must have been a technical issue with the experiment, but multiple replications confirmed that we had in fact stumbled upon a fascinating new process that reshapes our understanding of the hierarchical workflow of Polycomb complexes. We were dancing around the lab.”

The work was published in the journal Molecular Cell on Friday, providing a better understanding of Polycomb proteins, which are often mutated in cancers. Bracken’s team studies these mutations in childhood brain cancers and adult lymphomas to try and figure out the biological mechanisms that cause them. That way, the cancers can be targeted with more precise treatments.

“A firm and comprehensive understanding of the workings of these complexes is critical to figuring out new ways to target them in cancer settings,” Bracken said. “Therefore, this work led by Dr. Glancy and Dr. [Cheng] Wang in my lab will be built upon here and by other researchers worldwide to advance our approach to many cancers.”