Depression, one of the most prevalent mental health disorders worldwide, is characterized by persistent feelings of sadness, impaired daily functioning and a loss of interest in daily activities, often along with altered sleeping and eating patterns. Past research findings suggest that stress can play a key role in the emergence of depressive symptoms, yet the biological processes via which it might increase the risk of depression remain poorly understood.

Researchers at Wenzhou Medical University, Capital Medical University and other institutes in China recently carried out a study investigating the biological processes that could link stress to the onset of depression. Their results, published in Molecular Psychiatry, suggest that stress influences the levels of a chemical known as formaldehyde (FA) in specific parts of the brain, which could in turn disrupt their normal functioning, contributing to the emergence of depression.

The production of formaldehyde in the brain

Past studies have found that high levels of stress increase the risk of experiencing depression, particularly the most severe and persistent type of depression, known as major depressive disorder (MDD). Many patients with MDD also exhibit damage to the hippocampus, a brain region associated with memory and the regulation of emotions, and deficiencies in crucial chemicals known as monoamines.

Monoamines include serotonin, which regulates mood, sleep, digestion and impulse control, dopamine, which plays a role in motivation, reward and attention, and melatonin, the primary regulator of sleeping patterns. A reduction in these neurotransmitters could thus explain the disruptions in mood, sleep, appetite and motivation associated with depression.

Another chemical that could contribute to depressive symptoms is FA, a small and highly reactive chemical that is naturally produced as a byproduct of metabolic processes. Most notably, this chemical is known to be produced when the body breaks down DNA, RNA and histone proteins.

Earlier research has found that prolonged exposure to FA produced in the environment can cause depressive symptoms. Yet the possible effects of FA created inside the body had not yet been elucidated.

The research team at Wenzhou Medical University, Capital Medical University and other universities in China set out to fill this gap in the literature, specifically focusing on the possible impact of FA produced in response to stress.

“Surprisingly, the administration of FA causes depressive symptoms in both animals and humans, though whether endogenous FA induces depression is unclear,” wrote Yiqing Wu, Yonghe Tang and their colleagues. “We report that stress-derived FA promotes depression onset.”

Internally produced formaldehyde could disrupt mood regulation

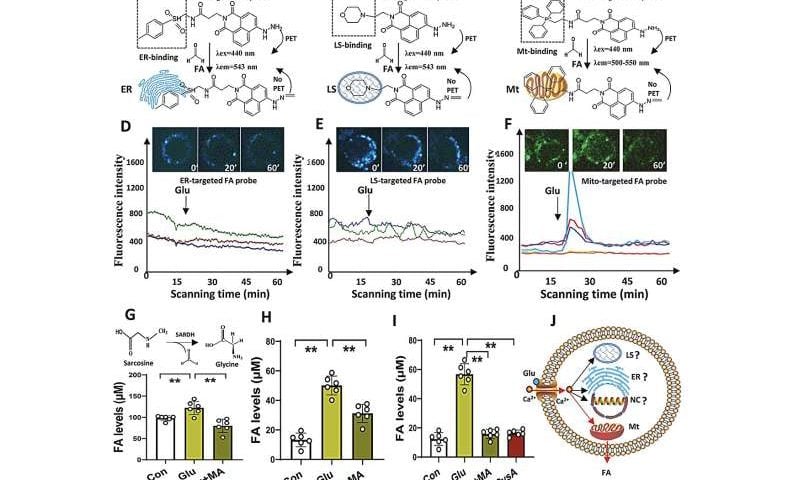

As part of their study, Wu, Tang and their colleagues used highly sensitive chemical probes to measure the levels of formaldehyde in the bodies of stressed mice and humans. The probes they used are essentially molecules that can be used to detect and measure the presence of target chemicals (in this case FA) as they emit light when interacting with these chemicals.

“Acute infusion and chronic FA injection were used to mimic depressive behaviors in mice under chronic unpredictable mild stress (CUMS),” wrote the authors. “Patch clamp recorded FA-inhibited hippocampal CA1 discharges, while mass spectrometry and spectrophotometry examined FA-inactivated monoamine.”

The researchers recorded the electrical activity in the hippocampus, as well as the levels of serotonin, dopamine and melatonin in the brains of mice. They then also analyzed magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans showing the brains of teenage patients diagnosed with MDD.

The researchers analyzed the blood of depressed patients and tried to determine whether the levels of FA in their blood were linked to the severity of their symptoms. They explored this connection further using computational tools designed to analyze biological data.

Finally, the team analyzed metabolomics data from a publicly available research dataset called MENDA (metabolomics encyclopedia for depression and anxiety). This is information related to the presence of specific chemicals in the bodies of individuals experiencing depression and anxiety.

The analyses carried out by Wu, Tang and their colleagues yielded interesting results, suggesting that acute and chronic stress can increase the production of FA in hippocampal neurons. This FA excess was found to be associated with the inactivation of serotonin, dopamine and melatonin, as well as the emergence of depression-like behaviors in mice.

“Our results showed that in cellular and mouse models, glutamic acid and both acute and chronic stress triggered FA production in hippocampal CA1 neurons,” wrote the authors. “Excessive FA induced depressive behaviors due to FA buildup and decreased serotonin, dopamine, and melatonin levels in the extracellular space. Especially, excessive FA deactivated these monoamines, damaged hippocampal CA1 structure, and reduced neuro-excitability.”

Possible clinical implications

This recent study sheds new light on the neurobiological processes via which higher stress levels could drive the onset of depressive symptoms. It particularly highlights the effects that a stress-induced excessive production of FA can have on the brain and body chemistry of both mice and humans.

“Remarkably, adolescent MDD patients showed hippocampal CA1 atrophy and monoamine deficiencies, with blood FA levels predicting depression severity,” wrote the authors. “These findings suggest that stress-derived FA serves as a critical trigger of depression by inactivating monoamines and impairing hippocampal CA1.”

In the future, the results gathered by these researchers could inform the development of new diagnostic tools or treatments for depression designed to limit the production of FA in the body and its overall effects on the brain. In addition, they could pave the way for further research probing the link between FA and depression.