While a couple companies are making waves in gene editing, Beam Therapeutics is swimming in a different direction with the budding technology to help reset the immune system.

The company is joining forces with Apellis Pharmaceuticals to create new gene-editing treatments for complement-driven diseases, a broad bucket of ailments caused by an overactive part of the immune system.

Under the five-year deal, Beam will pick up $50 million upfront and $25 million a year down the line. The duo will use Beam’s base-editing technology to discover new treatments against various targets in the complement system, named so because it helps—or complements—antibodies and white blood cells fending off invading pathogens. Problem is, when this system goes into overdrive, it can turn against body’s healthy tissues, causing inflammatory and autoimmune diseases.

The deal comes days after Intellia Therapeutics unveiled first-in-human gene editing results showing for the first time that genes could be edited successfully inside the human body. The news set off a wave of excitement for other companies in gene editing, including Beam.

Beam and Apellis will work together on six programs aimed at the complement protein C3 and other targets in the complement pathway for the treatment of diseases of the eye, liver and brain. The partners may choose to extend the partnership for up to two years for any or all six of the programs. And if Apellis chooses to license any of them, it will be on the hook for development, regulatory and sales milestone payments. The duo is keeping those details under wraps.

The deal is a natural evolution for Apellis, which decided years ago to stick to complement.

“When we went public in 2017, we decided we were going to try not to be distracted by anything else and focus on complement pathways and focus initially on complement factor C3,” said Apellis CEO Cedric Francois, M.D., Ph.D.

The company is developing its lead C3 inhibitor pegcetacoplan for several diseases, snagging its first FDA nod for the treatment of the rare blood disorder paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria in May this year. But that is just the tip of the iceberg for Apellis, which has been cooking up the deal with Beam for nine months, Francois said.

“What if we started using gene editing to rebalance homeostatic systems that have gone out of balance? So many of the diseases we have are the consequence of long-term dysregulation,” Francois said.

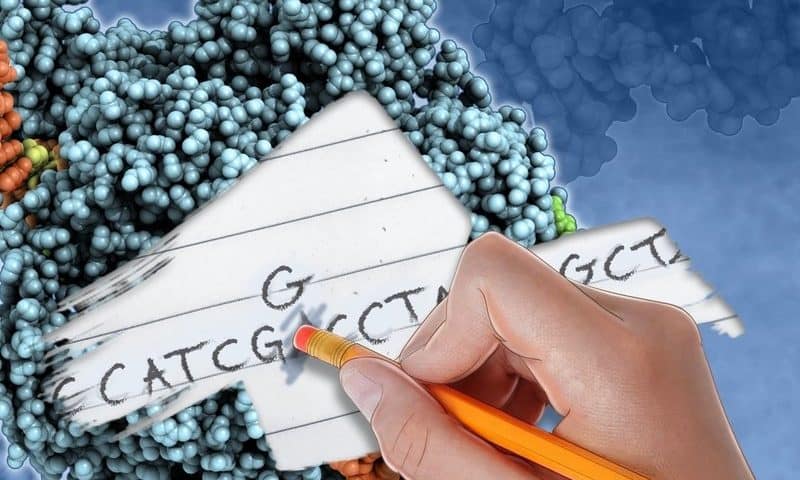

Beam’s base editing is the right tool for the job because it allows for precise editing without cutting through the DNA. “Traditional” CRISPR-based editing, like that used by Intellia, is often called “molecular scissors,” because it cuts both strands of DNA and relies on the cell’s processes to repair that break. Beam’s technology is more like a pencil that changes one nucleotide base, or “letter,” in the genome at a time.

“We can now do a wider range of manipulations of biology and genetics using very precise changes,” said Beam CEO John Evans. “We can silence genes without cutting, we can activate things, we can modulate a protein function. We can tune in a homeostatic way, up and down, the activity of a given protein.”

When Beam launched in May 2018, it highlighted point mutations, where a single base in a sequence is changed, inserted or deleted, as a natural target for base editing. But through partnerships with Verve Therapeutics and now, Apellis, the company is applying its tech to more complex diseases that aren’t necessarily caused by genetic mutations.

“Genetics and the way we think about genetics is much greater now than rare, genetic diseases,” Evans said. “Thinking about what we learn from population genetic studies about different variants and how they influence biology in a given direction … that is going to inform the way we use gene editing to create an increasingly large array for one-time therapies.”

Beam’s partner Verve is already working on a one-and-done base-editing treatment for high cholesterol. The treatment is designed to lower cholesterol levels by blocking the PCSK9 gene. Its first indication is an inherited form of high cholesterol called heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia, or HeFH, but the company plans to branch out into bigger patient populations, including “the more garden variety” atherosclerotic heart disease, CEO Sekar Kathiresan, M.D., said in an interview earlier this year. After that, Verve hopes to move into the preventive setting.