China is downplaying the political implications of its global development campaign known as the Belt and Road initiative, saying that it aims to boost multilateralism amid protectionist trends.

BEIJING — CHINA downplayed the political implications of its global Belt and Road infrastructure initiative, saying Friday that it aimed to boost multilateralism amid protectionist trends in the U.S. and elsewhere.

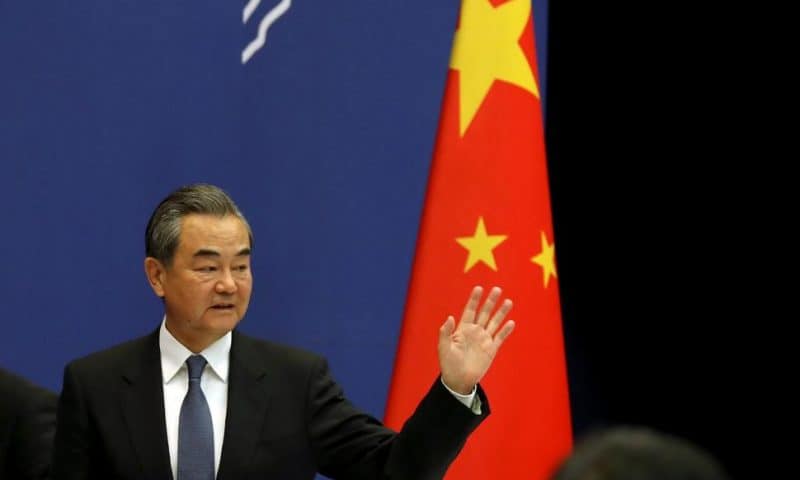

Foreign Minister Wang Yi said that a conference to promote the initiative to be held next week in Beijing would draw leaders from 37 countries, underscoring heavy demand for Chinese investment.

“The Belt-and-Road Initiative follows the principle of cooperation and collaboration with shared benefits. It embodies the spirit of multilateralism,” Wang said at a news conference.

Chinese President Xi Jinping, who has made the initiative a signature policy, agreed last month to seek fairer international trade rules and address the world’s economic and security challenges, in what appeared to many as a rebuke to President Donald Trump’s protectionist policies. Xi is to address the meeting’s opening ceremony on April 28, and chair a round table meeting of state leaders the next day.

The estimated $1 trillion-plus initiative aims to weave a network of ports, bridges and power plants linking China with Africa, Europe and beyond. It obtained a major symbolic boost last month when Italy signed a memorandum of understanding supporting the initiative, making the country the first member of the Group of Seven major economies to do so.

The U.S., another G-7 member, has been a notable critic of the initiative amid trade tensions with Beijing and competition over influence within global organizations, territorial claims in the South China Sea and the future of Washington’s ally Taiwan, which China claims as its own territory.

China’s expansion of the initiative in Latin America to build ports and other trade-related facilities has also stirred alarm in Washington over Beijing’s ambitions in a region that American leaders since the 19th century have seen as off-limits to other powers. China is focusing on countries in Central America such as Panama, whose canal linking the Atlantic and Pacific oceans makes it one of the world’s busiest trade arteries and strategically important both to Washington and Beijing.

The U.S. and some economists contend that the initiative forces emerging economies to take on unsustainable levels of debt to fund Chinese-backed projects, and Malaysia this week announced changes to a rail link agreement after the contractor, China Communications Construction Company Ltd., agreed to cut the cost by one-third.

Other countries have also put Chinese-funded projects on hold, hoping to avoid the fate of Sri Lanka. The South Asian country leased the Chinese-built port in Hambantota, which is near the world’s busiest east-west shipping route, to a Chinese firm in 2017 for 99 years in a bid to recover from the heavy burden of repaying a loan obtained the country received to build the facility.

China’s main Asian economic rival, India, has also turned a cold shoulder to the initiative, amid an ongoing border dispute between the two and competition for foreign markets.

In his comments, Wang sought to reach out to New Delhi, saying “achieving common prosperity” was a foundational principle behind Belt and Road and that “issues left over by the history must be separated from our efforts in this area.”

“I think such cooperation will not undermine India’s basic position on sovereignty and territorial integrity and at the same time, will provide opportunities of development and help India in the modernization endeavor,” Wang said.