Computer historians have staged a re-enactment of World War Two code-cracking at Bletchley Park.

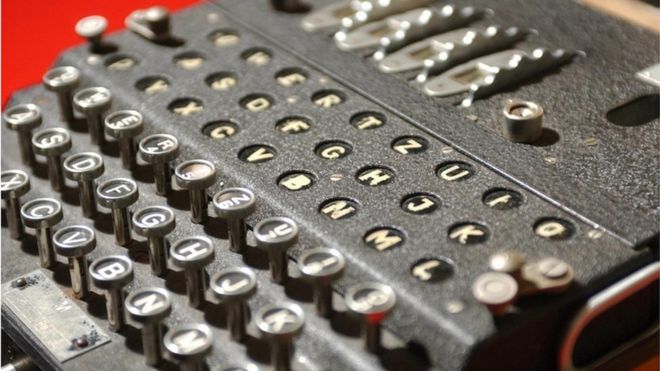

A replica code-breaking computer called a Bombe was used to decipher a message scrambled by an Enigma machine.

Held at the National Museum of Computing (TNMOC), the event honoured Polish help with wartime code-cracking.

Ruth Bourne, a former wartime code-cracker who worked at Bletchley and used the original Bombes, oversaw the modern effort.

Broken message

Enigma machines were used extensively by the German army and navy during World War Two. This prompted a massive effort by the Allies to crack the complex method they employed to scramble messages.

That effort was co-ordinated via Bletchley Park and resulted in the creation of the Bombe, said Paul Kellar who helps to keep a replica machine running at the museum. Renowned mathematician Alan Turing was instrumental in the creation of the original Bombe.

“During the war, they had about 200 Bombes,” said Mr Kellar. “It was a real code-breaking factory.”

For its re-enactment, TNMOC recruited a team of 12 and used a replica Bombe that, until recently, had been on display at the Bletchley Park museum next door.

The electro-mechanical Bombe was designed to discover which settings the German Enigma operators used to scramble their messages.

As with World War Two messages, the TNMOC team began with a hint or educated guess about the content of the message, known as a “crib”, which was used to set up the Bombe.

The machine then cranked through the millions of possible combinations until it came to a “good stop”, said Mr Kellar. This indicated that the Bombe had found key portions of the settings used to turn readable German into gobbledygook.

After that, said Mr Kellar, it was just a matter of time before the 12-strong team cracked the message.

Ms Bourne, who worked at Bletchley, said authentic methods had been used by the modern code-breakers but the effort lacked the over-riding stress and tension that accompanied the wartime work.

“During the war, there was a feeling of great pressure because the Enigma [encryption] keys changed at midnight so everyone was pushing to get enough information before it went out of date,” she told the BBC.

“The only high spot was when your machine happened to find the ‘good stop’ and you felt pleased about that,” she said.

Work on cracking the Engima machine was greatly aided by Polish cryptographers, said Mr Kellar. Friday’s event commemorated 80 years since that information was shared with the Allies. In addition, he said, the early stages of the code-cracking re-enactment were broadcast live to a Polish supercomputer conference in Poznan.