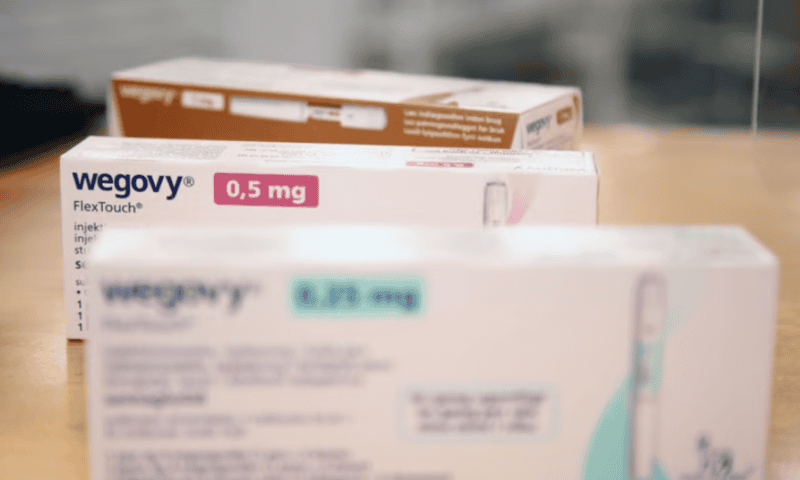

Outside of a global pandemic, it’s rare for a medicine to truly become a household name. But Novo Nordisk’s Wegovy is rapidly reaching that status, with the obesity drug accruing more front pages and celebrity endorsers every day.

The success of the GLP-1 agonist, originally known as semaglutide and later branded as Ozempic to treat diabetes, means analysts expect the Danish Big Pharma to stake out a GLP-1 market totaling $33 billion by 2030. It’s already been enough to turn Novo Nordisk into Europe’s highest valued company last month, with an eye-popping market cap of $309 billion.

But that influx of cash brings with it increased interest in the wider Novo organization—a series of entities the lower profiles of which belie both their impact on biotech and their increasingly global ambitions.

Sitting atop the Novo edifice is the Novo Nordisk Foundation, which made over 1 billion euros ($1.05 billion) worth of philanthropic grants and investments last year alone. And that’s just the start—according to the independent foundation’s latest presentation, it expects that outlay to almost double by the end of the decade.

But if you’ve never heard of this philanthropic giant redistributing funds from one of the world’s biggest pharma players, then don’t worry, you’re not alone. When Novo Nordisk Foundation CEO Mads Krogsgaard Thomsen, Ph.D., met Bill Gates for the first time, the billionaire philanthropist “said, ‘Most of what I know about your foundation is that your company makes Wegovy,’” Thomsen remembers.

Since that first meeting at Davos, the Novo Nordisk Foundation and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation have joined forces to tackle two of the major issues of our times: the creation of new antivirals that could stave off a future pandemic and ways to utilize CO2 to produce proteins for human food.

It all sounds far removed from Novo Nordisk’s day-to-day therapeutic activities, which don’t stray into infectious diseases let alone the cutting-edge world of electrochemical food production. However, Thomsen himself has deep roots at the Big Pharma, having spent 30 years at the company including two decades as chief scientific officer.

Since moving to the foundation in 2021, he has overseen a slew of clinically focused initiatives. They include funding a major international center for stem cell medicine research as well as the launch of the Novo Nordisk Foundation Institute for Vaccines and Immunity, which Thomsen explains is tasked with “actually finding vaccines and taking them into the clinic.”

In his Copenhagen office, decorated with relics from Novo Nordisk’s century of pharmaceutical breakthroughs, Thomsen explains to Fierce Biotech that his self-appointed mission when joining the foundation was to draw together the organization’s disparate research work and make it “more mission driven, more strategic.” The philanthropic nature of the foundation means that whether it’s stem cell therapies or vaccines, the goal is to do good rather than worry about turning a profit.

“We’re not a commercial player, because once that cell therapy matures and we have phase 1/2 data that are intriguing and promising then the idea is, of course, to hand it over—either to a new company that can be formed and create welfare and jobs in Denmark or to an existing company,” he says. “It could be Pfizer, it could be Novo, it could be anyone.”

A major player in biotech investments

The money the foundation is planning to hand out doesn’t come direct from Novo Nordisk but via another entity called Novo Holdings. As well as being the controlling shareholder of the Big Pharma, the fund manager’s role is to take the revenues from Novo Nordisk and make that money go further.

To that end, Novo Holdings invests in the ballpark of $500 million a year, mainly in private and publicly listed life sciences companies around the world. So far, more than 160 biotechs and other companies have benefited from the fund manager’s investment dollars, making it a major player in the VC ecosystem.

The influx of cash from semaglutide’s newfound success may mean that the fund manager can “scale up” the amount of money available for biotech investments “a little bit more,” Novo Holdings CEO Kasim Kutay tells Fierce in his own office on the other side of the foundation’s building.

But while semaglutide revenues could bring “a hell of a lot of money” his team’s way in the coming years, he downplayed the suggestion that this would significantly alter Novo Holdings’ biotech investment strategy. “We’ve developed our teams in a way that we are very responsible in how we deploy that capital, and I feel the responsibility more than ever,” Kutay says.

One way we may see Novo Nordisk’s commercial success filter down is in the continued expansion of Novo Holdings’ geographic footprint. In recent years, the fund manager has opened offices in the U.S. biotech hubs of Boston and San Francisco as well as London, Singapore and Shanghai.

“In the next five years we may add another one or two locations,” Kutay says. “But I think for now we’re in the most important ones from our perspective and from where we want to deploy capital.”

Novo Holdings currently employs around 160 employees, with that number set to rise to around 180 by year-end. “I think there’ll be a little bit more growth after that,” he adds. “But … I think once we get to 180, that gives us a lot of scope.”

Novo Holdings has already been involved in a number of biotech megarounds this year, including Amolyt Pharma’s $138 million series C, which the French company is using to push its hypoparathyroidism drug through phase 3 trials, and Switzerland’s Alentis Therapeutics, which completed a $105 million series C to fund trials of its anti-Claudin-1 antibodies for tumors and organ fibrosis.

Despite being run at arm’s length from Novo Nordisk, the fund manager does try to “avoid playing in the same sandpit” as the Big Pharma by steering clear of disease areas like diabetes or obesity, Kutay explains.

“If we’re uncertain, we just pick up the phone and say, ‘Look, does this conflict with what you’re doing in any way?'” he says. “If the answer is no, then we proceed.”

Yet, while Novo Holdings has Novo Nordisk’s profits to play with, Kutay explains that the way his team picks potential biotech investments is not influenced by Novo Nordisk’s overarching strategy.

“We are a 100% returns-driven investor,” he says. “There is no strategic component to what we do. We feel very proud that the more money we generate, then the more good the foundation can do.”

A European take on the Flagship model

While spending a morning in the Novo Nordisk Foundation’s sleek Danish offices, Fierce was also able to sit down with Søren Møller, Ph.D., who heads up Novo Holdings’ seeds investments team. With an annual investment budget of around $200 million, their job is to scout out exciting discovery stage and preclinical projects that can be spun out of universities or existing pharma. After helping out these fledgling biotechs, Novo Holdings become one of their biggest investors, following the companies through further rounds of their funding journey, Møller explains.

But unlike Novo Holdings more generally, Møller’s team has a much tighter geographic focus, preferring to build out biotechs with a footprint in the Nordics. It puts their attention thousands of miles away from the big U.S.-based biotech startup factories like Atlas Venture and Flagship Pioneering. Luckily, Møller doesn’t view that as a problem.

“I don’t see it as a big limitation, because the company creation model is very saturated, and Boston is very competitive, right?” he says. “I think where we can make a bigger difference is applying some of the models that they’ve been successfully creating in the U.S., and, with our pharma legacy and the skill sets around and the capital that we can deploy, do the European version.”

One good example of this model in action is Embark, an obesity-focused biotech that spun out from the Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research at the University of Copenhagen in 2017 with seed financing support from Møller’s team. Embark began collaborating with Novo Nordisk itself in 2018, before being snapped up by the Big Pharma in August this year.

Despite semaglutide’s ability to boost Novo Holdings’ coffers, Møller doesn’t expect his seed financing team to receive a bigger slice of the pie.

“I don’t think there’s a big material need,” he explains. “For our size of fund [and] our size of team, $200 million per year is a very good number. And I think it goes back to some questions on how much can you actually deploy?”

While Novo Holdings is already a major player in the biotech investment scene, the vision sketched out by both Thomsen and Kutay is much more expansive. While the majority of Novo Holdings’ investments to date have been in drug developers, Kutay suggests the ultimate goal is to spread their money equally between biotechs and new players in the burgeoning world of bioindustries. In fact, the fund manager has already recruited a specialist bioindustrials team to seek out potential investment opportunities.

While acknowledging it may be of less interest to Fierce’s readers, he singles out Novo Holding’s relationship with BioPhero as a “cutting edge” investment in this space that he’s proud of. The Denmark-based company has been working on using pheromones to create an alternative form of pest control to insecticides. Novo Holdings was onboard from the start, with the startup eventually selling for $200 million to agricultural sciences company FMC Corporation last year.

“It’s really taking this bioindustrial concept of bio-pesticides and seeding that company and investing in it and developing—and then selling it for a significant return,” Kutay says.

It’s a perfect example of how the Novo Nordisk Foundation wants to put its money to good use way beyond the life sciences while staying true to its Danish and pharmaceutical roots.

“I think now is the time for us to internationalize because, to be honest, we’re a very big foundation in a rather small country,” Thomsen says.

“It’s not that we are not big time funding the Danish ecosystem,” he adds. “But we have come to a maturity level where we want real solutions involving Danish science but also global science—because then you get the best.”