The protein BRAT1 regulates how cells respond when their DNA is damaged, and it’s known to help drive cancer. But it’s also considered “undruggable” because it lacks binding sites that synthetic molecules need to be able to inhibit it.

Scientists led by Purdue University say they’ve found a novel compound that can inhibit BRAT1—and that may make chemotherapy more effective at damaging cancer cell DNA.

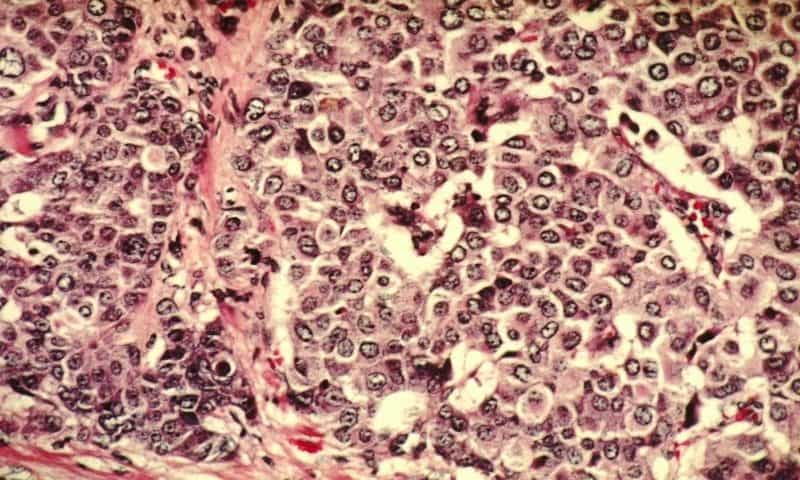

The team used curcusone D, a compound derived from the Jatropha curcas, a shrub known for its medicinal properties. A synthesized form of curcusone D inhibited BRAT1 in breast cancer cells, killing them, the researchers reported in the Journal of the American Chemical Society. It worked even better when combined with the chemotherapy drug etoposide.

In addition to killing cancer cells, curcusone D was able to stop them from metastasizing. Although there are other DNA-damaging drugs on the market to treat breast cancer, including some that stop them from migrating to other organs, there are none that inhibit BRAT1. Therefore synthesized curcusone D could prove useful in combination with cancer drugs that work via other pathways, the researchers suggested.

The quest to combat drug resistance in treating breast cancer has yielded a number of new targets. Earlier this month, for example, an Italian team identified two related microRNAs that could be inhibited to make breast cancer cells 20 times more sensitive to the chemotherapy drug methotrexate. And researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, published evidence that targeting the transcription factor NF-kB could be effective in the most aggressive form of the disease, triple-negative breast cancer.

The Purdue team worked with a group at Scripps Research Institute to link curcusone D with BRAT1. If the compound proves effective in further studies, it could be useful in treating other cancers in which BRAT1 plays an important role, including colorectal, lung and brain cancers, the researchers said.

As for the shrub that inspired the novel compound, it has been used in traditional medicine before and is thought to be safe, so the researchers are optimistic. “Many of our most successful cancer drugs have come from nature,” said Mingji Dai, a professor of chemistry at Purdue, in a statement. “A lot of the low-hanging fruit, the compounds that are easy to isolate or synthesize, have already been screened and picked over. We are looking for things no one has thought about before.”