Cancer cells survive and proliferate with the help of nutrients and other materials that reach the cell nucleus via the “nuclear pore complex”—a door of sorts that’s vital for tumor survival. But what if that door could be blocked or, better yet, prevented from forming in the first place?

That’s the hypothesis behind research at Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute. A team there is working on methods for preventing cells from building nuclear pore channels. Now, they have preliminary evidence that the approach works in animals.

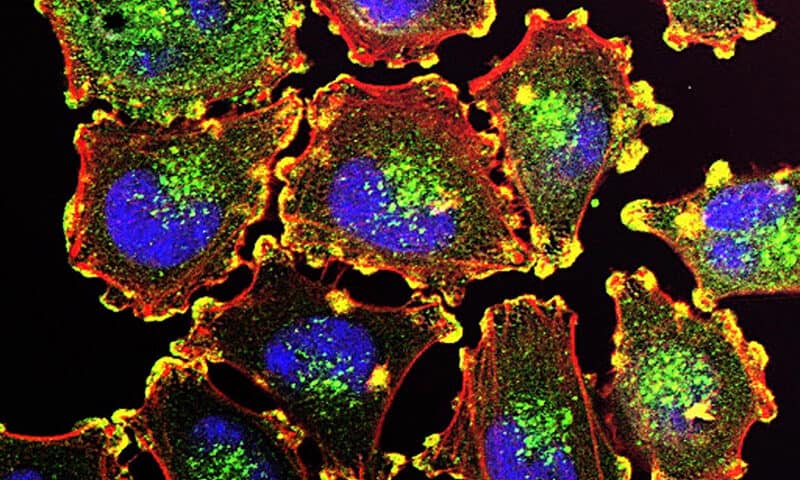

The Sanford Burnham Prebys researchers started with human tumor cells that couldn’t form nuclear pore complexes. The cells came from melanoma, leukemia and colorectal cancer—three cancer types that are known to be especially dependent on the complexes for their survival.

When the cells were transplanted into mice, the tumors remained small and slow-growing. The research was published in the journal Cancer Discovery.

“We showed that the inability to build nuclear pore channels is devastating for rapidly-growing cancer cells, but doesn’t seem to have an impact on healthy cells—which simply halt their growth, and then recover,” said first author Stephen Sakuma, a graduate student in the lab that’s working on the project, in a statement.

Finding new ways to control the transport of life-sustaining materials into cancer cells is the focus of several research groups. Last December, scientists at the University of Toronto discovered that the protein importin-11 transports the protein beta-catenin in the nucleus of colorectal cancer cells, fueling their growth. When they removed importin-11 from tumor cells, their growth slowed.

A research team at Northwestern University is focusing on how DNA, RNA and proteins of the chromosome, known collectively as “chromatin,” are packed into the nucleus of cancer cells. They reported last year that altering chromatin packing could make cancer cells more vulnerable to treatment.

The Sanford Burnham Prebys team is now working on searching for drugs that can prevent nuclear pore complexes from forming.

“Tumors would have a hard time adopting to an environment where their ‘doors’ are removed, so this drug might help certain treatments, such as targeted therapies, remain effective for longer periods of time,” said Maximiliano D’Angelo, Ph.D., associate professor of the development, aging and regeneration program at Sanford Burnham Prebys.