While AstraZeneca may be a major player in the oncology space, the company has been noticeably absent as the first wave of CAR-T therapies hit the market over the past five years. But movement is happening behind the scenes.

It turns out the U.K.-headquartered drugmaker has been quietly stockpiling the necessary knowledge and technology to make an AstraZeneca CAR-T a reality one day, according to Dave Fredrickson, executive vice president of AstraZeneca’s oncology business unit. In fact, a key part of the drugmaker’s longer-term cancer strategy is “building our own cell therapy expertise.”

“We’ve been working pretty diligently to build the capability set and start to get real progress made there,” he says. “I’m pleased with what I see.”

While it may seem late in the day to go head-to-head with now established CAR-T players like Novartis’ Kymriah and Kite Pharma’s Yescarta, AstraZeneca already has its eyes on the next generation of these cell therapies.

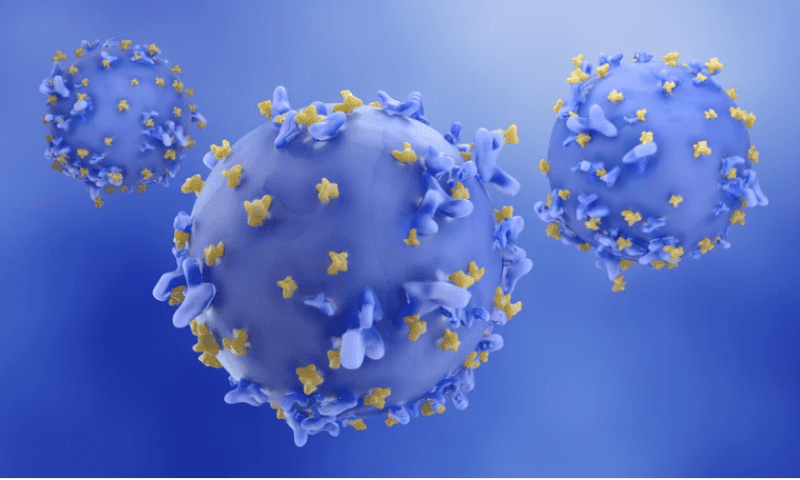

All approved CAR-Ts to date are so-called autologous treatments, meaning they are based on donations of a patient’s own cells. An up-and-coming class of CAR-Ts in various stages of clinical testing by different pharma companies are known as allogeneic, or “off-the-shelf,” therapies, because they use engineered cells collected from a third party.

“Like many, we are focused on two key things: can we really unlock science to be able to bring cell therapy to solid tumors above and beyond what’s already been done?” Fredrickson says. “And also: Can we have off-the-shelf versus autologous solutions?”

“We don’t see that we have to go pursue M&A in order to compensate for a pipeline that isn’t delivering organically.” — Dave Fredrickson, AstraZeneca

Targeting CAR-Ts in solid tumors is a widely held ambition among Big Pharma—Novartis told Fierce Biotech of similar plans in June last month. Speaking to Fierce in London on Friday following the announcement of AstraZeneca’s second-quarter results, Fredrickson acknowledges that the Cambridge, U.K.-based company is “not unique in that objective.”

He remains tight-lipped on further details, pointing out that all the cell therapy work is still at the pre-clinical stage.

“It’s early days, but that’s a longer-term set of investments that we’re making,” he says. “Stay tuned for more on the science that’s coming.”

So is the drugmaker looking for some high-value M&A to galvanize these fledgling CAR-T ambitions? “Our cell therapy work is really work that we’ve invested in to build organically within AstraZeneca,” Fredrickson explains. “This is not to say that as we do it, we won’t find partners that we want to be working with along the way.”

“We don’t see that we have to go pursue M&A in order to compensate for a pipeline that isn’t delivering organically,” Fredrickson says at another point. “We’ve got our own R&D that we’re really enthusiastic about, but we’re always looking outside to make sure that we’re not missing a trick.”

As an example of the Big Pharma’s track record hunting down the right cancer deals, he points to the “tremendous success” of the 2015 acquisition of Acerta, which brought on board lymphoma drug Calquence. The strong performance of Calquence in turn allowed AstraZeneca to scoop up T-cell engaging bispecific antibody developer TeneoTwo for $100 million last month, Fredrickson adds.

ADC ambitions

Off-the-shelf CAR-Ts may be getting hearts racing across Big Pharma, but ask Fredrickson which cancer project gets him out of bed in the morning and you’ll discover it is in fact antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs).

“I get the most excited about projects that progress from … preclinical to clinical,” he says. Fredrickson highlights the landmark clinical trial win in breast cancer for the Daiichi Sankyo collaboration Enhertu, which could soon open up a brand-new breast cancer category for the approved medicine and offer HER2-targeted therapy for many patients with what have traditionally been characterized as HER2-negative disease.

“When I look at Enhertu, this has the opportunity to be one of the most significant medicines in oncology and it really is delivering what has been an unfulfilled promise of antibody drug conjugates today,” Fredrickson says.

Another ADC co-developed with Daiichi called DS-1062, which targets the glycoprotein TROP2, is currently in a late-stage study for non-small cell lung cancer, with the aim of beating the chemotherapy docetaxel.

“I’ve got a lot of optimism that we’re going to see success out of that,” Fredrickson says. “Anything that we can do to displace systemic chemotherapy with something more efficacious gets me enthusiastic.”

AstraZeneca hasn’t just been relying on Daiichi to provide a steady stream of ADCs, however. The company is “rapidly developing and advancing” its own portfolio, Fredrickson points out.

In the previous quarter’s earnings, AstraZeneca singled out one of these in-house ADCs, dubbed AZD8205, which is in an early-stage study for a range of cancers including breast, ovarian and endometrial.

“We’re really pleased to say that we’ve now got several [in-house ADCs] that are in phase one, and we think that we’ve got very competitive technology that we’re working on there,” Fredrickson says.

Across its existing oncology portfolio, AstraZeneca is best known for therapies targeting lung, breast and ovarian cancer. But the drugmaker has been widening its gaze to include the likes of gastrointestinal and genitourinary tumors, Fredrickson explains.

“We’ve moved from a focus on maybe two tumor types to now six different major tumor types,” he says.