GlaxoSmithKline’s scientific champions, Hal Barron, M.D., and Tony Wood, Ph.D., were with LifeMine Therapeutics before the small, fungi-focused biotech knew what it does now. Those early conversations, which began two years ago, have led to today: a $70 million upfront deal to develop three candidates based on LifeMine’s fungi-based drug discovery engine.

CEO Greg Verdine, Ph.D., called the GSK deal his “dream scenario” in an interview with Fierce Biotech, as the company announced the deal plus a $175 million series C fundraising. GSK contributed to the round, which was led by Fidelity Management & Research Company, plus existing investors Arch Venture Partners, MRL Ventures Fund and more, as 3W Partners Capital, Invus and others joined as new investors.

Verdine said GSK—particularly Barron, who recently announced his departure as chief scientific officer, and Wood, who will replace him—were there from “out the starting gate” of LifeMine’s technology.

“They were an early adopter, when we hadn’t really quite figured out everything that we’ve figured out now,” Verdine said of Barron and Wood.

The pair helped broker not just today’s deal, but also helped build LifeMine into the company it is now. Verdine expects the biotech’s first major pharma deal will open doors to others down the road—and he’d like a few more to fill up the pipeline but not overload the staff. Barron is expected to stay on with GSK through at least August and then transition into a non-executive board role, so the work with LifeMine continues, Verdine said.

Through the new partnership, which actually got underway in December 2021, GSK will bring three targets for LifeMine to run through its proprietary drug discovery platform, which scans for fungi that could be a match to create a small-molecule drug.

The companies will share costs 50-50 during the discovery process and up to the filing of investigational new drug applications with the FDA. Then, GSK will take over and fund all development and commercialization efforts. The companies did not disclose which indications or disease areas they will explore, and Verdine said the direction is “TBD.” LifeMine has initially focused on oncology and immune modulation, however. The deal also includes undisclosed milestones and royalties.

The series C, on the other hand, will allow LifeMine to “build a pipeline,” Verdine said. He expects the company to have two development candidates selected by the end of this year with INDs filing late 2023 or early 2024.

Besides designating therapies to move into the clinic, funds will go toward hiring key executives, including a chief data officer, a chief medical officer and more. LifeMine also plans to expand to a third research site in Basel, Switzerland, that is 40,000 square feet, beyond existing locations in Gloucester and Alewife, Massachusetts. The Basel site will focus on chemistry.

Verdine expects that two years from now, LifeMine will have a stocked pipeline and the GSK partnership will begin to bear fruit with IND discussions getting started.

Fungi and Tom Brady

Small molecule drugs are, of course, not new, but the way LifeMine turns up potential meds is, Verdine said.

“One of the biggest problems in drug discovery right now that nobody’s figured out how to fix is, we are awash in targets,” Verdine said.

That’s because of the efficiency of human genomic sequencing, CRISPR and other technologies that have helped drug companies screen for potential targets to go after with medicines. But quantity does not mean quality: Verdine says drug discovery has a 90% failure rate.

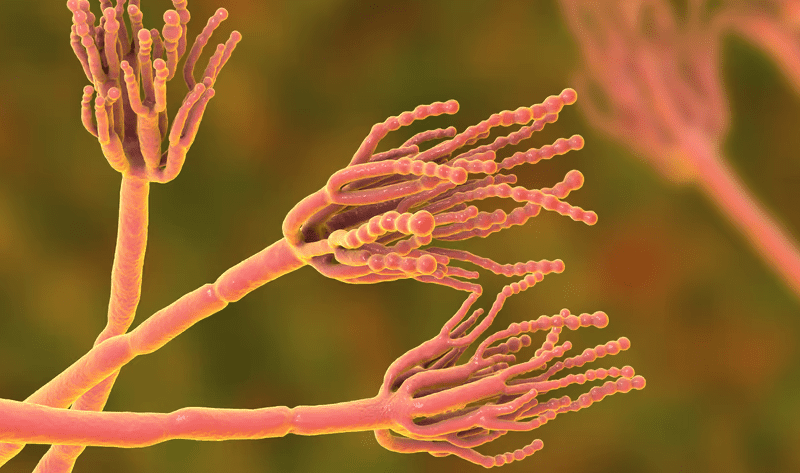

So, LifeMine has a library of 65,000 deep-sequenced wild type fungi and algorithms that scan entire genomes to discover a potential small molecule to match up with a target.

Fungi-based drug discovery has long been of interest to Big Pharma, but many companies, with the notable exception of Novartis, have gotten out of the field.

“Big Pharma always liked the molecules, but what they didn’t like is the extreme inefficiency of discovering them,” Verdine said.

Novartis now has a small group working on naturally occurring small molecules. The challenge was immense: A single fungi extract may have 5,000 different molecules, and the company may have that many or more different targets to test against.

“So pharma gave up on it,” Verdine said. LifeMine acquired its sample library from the likes of Pfizer (via Wyeth), Merck, Schering (later Bayer), and others. It scans that library using machine learning, AI and other technology to make the job easier. Advancements in science have also made the whole process more targeted.

“[The samples] were painstakingly collected by microbiologists over 30 years ago, and we went out and acquired them. … [T]hese are living organisms,” Verdine said. “This resource has an extremely limited availability anywhere else, and we’ve made sure that we secured as many of them as we can.”

Meanwhile, LifeMine has worked to collect its own as well; at the Gloucester site, the biotech is collecting marine fungi.

Verdine likens the fungi drug class to Tom Brady, who “every once in awhile gets possession in the end zone.” What he means is, well-known fungi-based drugs like penicillin, cyclosporine or mycophenolic acid and a few others are rare exceptions that “went straight from the fungus right to the patient.”

“We’re not counting on that happening … but we’re getting the ball on the 90-yard line,” Verdine said. The company’s technology can go from a digital genomic search to an advanced lead in about six months, he explained. The quickest they’ve ever turned up a valuable candidate was four and a half months, he said.

Cutting down on the failure rate in drug discovery is exactly what GSK is after with this deal. The U.K.-based Big Pharma has already been using advanced technologies, including human genetics, in its drug discovery efforts to increase the probability of success, said John Lepore, M.D., senior vice president and head of research. The LifeMine partnership will allow the companies to work together to “identify what nature might have already created as chemistry starting points to increase our chances of developing transformational new drugs for patients,” he said.

As for where LifeMine might go after the series C financing, Verdine—who’s launched 10 biotechs and is also currently president and CEO of FogPharma—said he’s “a little conservative about IPOs.” And that’s not necessarily because of the recent downturn that has faced nearly every company that’s gone public over the past year. He’s seen mixed results on going public at the companies he’s overseen.

“I’ve seen [companies] that did well from being a public entity … and then others that I think labored under the weight of having to disclose every single thing that you’re doing,” Verdine said.

He’d prefer a company to have validated preclinical data or a plan to get into the clinic before an IPO is on the table. So, while he wouldn’t commit to an IPO for LifeMine, Verdine said they’ve built the company with funding to get them into the clinic and new pharma partnerships could help along the way as well.

“The one thing that I’ve learned is, if you’re building a substantial company and you’re focused on substance, that you have all kinds of financing options, and it becomes really a question of what’s the most effective for building the company,” Verdine said.