Fears over Brexit and renationalisation are spooking the private global investors in formerly state-owned utilities

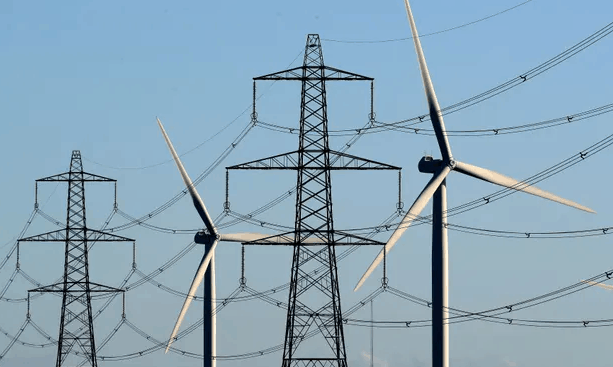

Energy suppliers may be on the frontline of the battle to win public trust in the industry, but it is the companies behind the gas pipes and electricity wires which have emerged as the easiest political targets.

The network operators, including National Grid and UK Power Networks, are facing a fierce political skirmish. The industry regulator has already cut the returns they are allowed to make to all-time lows. An even greater risk looms beyond the next general election, now that Labour has pledged to bring the companies back under public control.

Critics of the firms argue that the crackdown is an inevitable consequence of the years they have spent “inflating” household energy bills while siphoning off billions in dividends for their international investment-fund owners. They are held up, alongside water companies and rail operators, as evidence of Britain’s failed experiment with privatisation.

The companies are quick to point out that the prices they levy through energy bills have fallen 17% since the sector was liberalised in the 1990s, while private investment has climbed to about £100bn over the period. Renationalising would mean less investment and higher bills, they say. But as their economic defence falls on deaf ears, the operators of Britain’s energy infrastructure are becoming jittery.

John Pettigrew, National Grid’s chief executive, has warned that there are deepening concerns over the UK’s political landscape, particularly among the company’s international investors. “When I talk to our investors overseas, what is important to them is a stable regulatory and political environment. The debate on state ownership has them increasingly concerned,” he said.

Pettigrew joined National Grid as a graduate in 1990, just weeks after privatisation. Almost 30 years later, the free-market holy grail is tarnished by a deep mistrust of private investors and rip-off capitalism.

Today, Pettigrew is steering one of Britain’s most high-profile examples of liberalisation away from the UK and towards the United States.

The FTSE 100 company undertakes the same work it carries out in the UK across 9,000 miles of US electricity transmission cables in five north-eastern states. The US is a market which generates more revenue for the company than the UK, with less political risk, and stands to attract most of its future investment too.

Pettigrew said earlier this year that National Grid planned to increase its investment in its frontier market from $3.5bn (£2.9bn) in the 2018-19 financial year to $5bn. It already employs more than double the number of employees in the States than it does in the UK, and it expects the business to grow beyond gas pipes and electricity lines too.

Earlier this year, National Grid tied up a $100m deal to acquire US renewables company Geronimo through National Grid Ventures, its new venture-capital fund based in Silicon Valley. The innovation arm now owns a string of wind and solar farms and plans to fund new tech startups in the US with an initial investment of $250m over the next two years.

The American market offers a safe haven for National Grid’s investments that lie beyond political upheaval. But it is also a market in which Pettigrew can expect stronger growth, and support from state officials to upgrade the grid and add electric-vehicle charge points.

One senior industry boss, who asked not to be named, said major international investors were looking elsewhere too. “Investors are looking at the UK right now and asking whether it is the right time to be investing in any kind of regulated utility in the UK,” he said. “Investors consider two things: the opportunity and the environment. The UK’s decision to create a net-zero-carbon economy is a colossal opportunity, but the environment has given investors pause for thought.”

Even those investors who believe a Labour government may pay a fair price for their assets in the event of renationalisation are concerned about draconian regulation and the threat of a no-deal Brexit: “The problem is that the need for investment in the energy industry is now.”

The UK government’s strong support for building offshore wind turbines and electric vehicles will still need investment in the pylons, substations and powerlines which connect renewable energy to homes and charge points, industry sources say. The need to wean households off fossil fuels for home heating could require even more ambitious work to overhaul the country’s gas grids too.

“The most critical thing about net zero carbon is about the speed of delivery – the last thing anybody should be thinking about doing is slowing this industry down,” the energy boss warned.