Researchers have used stem cells to develop new human embryolike structures that model the earliest stages of fetal development so realistically that they even secrete hormones that can turn a lab pregnancy test positive.

In a study published Sept. 6 in Nature, which followed a preprint in June, an international team of scientists led by researchers from Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel described how it used genetically unmodified pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) to develop a model of the structure of a human embryo from implantation to around 14 days after fertilization. Eventually, it could allow researchers to better understand birth defects as well as the factors that lead to miscarriage, which, in about 80% of cases, occurs within the first 12 weeks of pregnancy.

“For the first time we generated without sperm, egg or uterus an embryo-like structure up to day 14,” Jacob Hanna, M.D., Ph.D., told Fierce Biotech Research in an email. “It is the first time a human embryo model is made with structural organization or that contains all lineages including the surrounding placenta, and has made all known compartments of that stage that have never been recapitulated before in a dish. That is why we are very excited about this.”

The nuances of the earliest phases of human development still hold many mysteries, as there has historically been no high-quality model with which to study them. Previous attempts lacked the defining characteristics of a post-implantation embryo, namely the many cell types that are required to form the placenta and other critical elements. They also weren’t organized in a way that would allow them to progress to the next stage of development.

Without a model, the early human embryo remained something of a black box. “Stem cell scientists want to study closely the human embryo from one to five weeks because this is when the embryo makes all its organs,” Hanna said. “This is inaccessible in humans for ethical reasons [and because in] the early stage, the in vivo embryo is too small … it’s a big problem.”

That changed last year, when Hanna’s team showed that it had successfully used mouse PSCs to create a murine embryo model that was capable of developing what they described as a “beating heart-like structure.” These weren’t just any PSCs, though: They were naive PSCs, meaning they had been reverted back to an earlier developmental time than typical stem cells. Hanna’s lab became the first to describe a technique to create human naive PSCs back in 2013.

“Both mouse and human protocols rely on starting with naive cells, which means they are placed in a special media that keeps them in a very, very early stage, so they have unlimited potential,” Hanna told Fierce. Since last year’s mouse study from Hanna’s lab, a team of scientists based in China has grown synthetic primate embryos. Notably, neither the mouse nor primate models continued developing when transferred into a womb, though some of the monkeys did show some initial pregnancy signs.

The new study builds on that work, this time with human naive PSCs. In this case, the cells were either derived from adult skin cells that had been reverted into PSCs or came from human stem cell lines that had been cultured for years in Hanna’s lab. They were transformed into naive PSCs using the lab’s established technique, then divided into three groups—one that was left untouched and another two that were treated with chemicals that would help them differentiate into essential tissues.

The cells were then mixed together under specific conditions to help them mature into embryos. About 1% went on to form embryolike structures that secreted human chorionic gonadotropin, the hormone detected by commercial pregnancy tests. Indeed, putting the secretions on such a test turned it positive, the researchers reported in the paper.

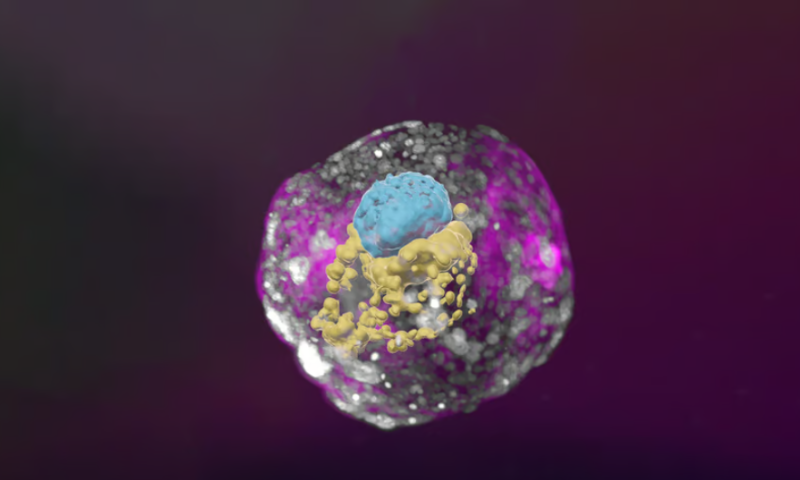

The synthetic human embryos aren’t completely identical to real ones, of course—like the mouse and monkey models, they wouldn’t grow if they were implanted into a womb. But they do include key hallmarks of the earliest prenatal period, like the epiblast, hypoblast, extraembryonic mesoderm and trophoblast, layers of tissue that ultimately form the basis of organs and placenta.

In comments provided to the U.K.’s Science Media Centre, some scientists unaffiliated with the study noted that while it was indeed a major step forward, the process to create the embryos remains inefficient.

“Despite being a significant stepping stone … the protocols have a relatively low efficacy,” Darius Widera, Ph.D., a professor of stem cell biology and regenerative medicine at the University of Reading, told the organization. Still, he also noted that the structures “could generate valuable insights into the processes governing early human development and potentially provide new insights into certain factors that contribute to miscarriage in humans.”

To that end, the scientists in Hanna’s lab may have already stumbled upon a new factor in the course of growing the embryos. They saw that if the embryo was not surrounded by cells that form the placenta by Day 3 of the protocol, which aligns with Day 10 of natural development, other structures fail to grow.

“An embryo is not static. It must have the right cells in the right organization, and it must be able to progress—it’s about being and becoming,” Hanna said in a press release from the Weizmann Institute. “Our complete embryo models will help researchers address the most basic questions about what determines its proper growth.”

Hanna’s lab is among several attempting to build human embryo models. As they do, they’ll need to address some ethical questions as well, which may lead to regulatory ones. In the U.S., the National Institutes of Health doesn’t allow funding for the creation of human embryos or embryoids for research purposes, though it has funded mouse embryo development. Some scientists have called this rule into question, noting that infertility clinics dispose of unused embryos as medical waste.

Pompeu Fabra University Professor Alfonso Martinez Arias, Ph.D., whose own lab is working on building human embryo models, noted that such conversations are nothing new.

“I expect the work to raise ethical issues but, unlike earlier claims, this time with a real basis to think about the questions that emerge,” he told the Science Media Centre. “Nevertheless, it is important to state that as surprising as the emergence of the structure is, this work is not unexpected and the scientific community has been anticipating these developments for the last few years and have ongoing discussions on the subject geared towards regulation of this type of research.”