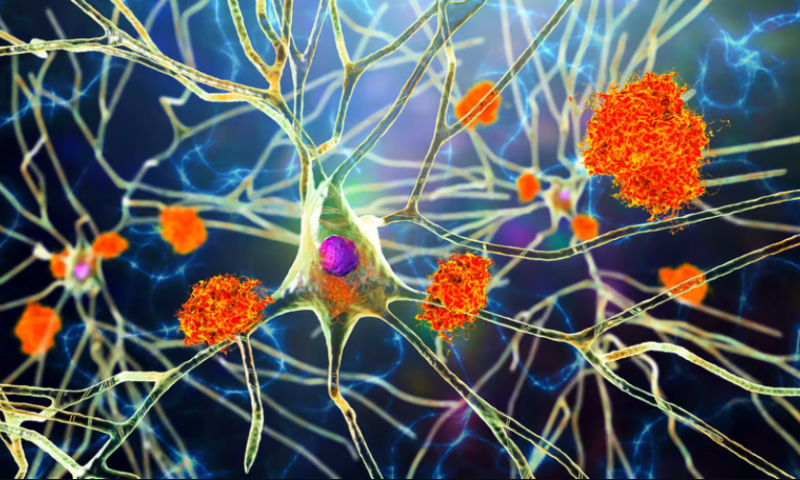

The buildup of amyloid beta plaques in the brain has long been associated with the development of Alzheimer’s disease, making them a frequent target for novel treatments of the neurodegenerative illness.

But what if drugs built to limit plaque buildup are targeting the wrong area? New research suggests the origins of the plaque may predate the misfolded protein that has guided recent therapeutic approaches.

That’s the top-line conclusion of a new study published by a team of scientists from NYU led by Ju-Hyun Lee, Ph.D., which identified intracellular pit stops in handling cellular waste as the potential origin of amyloid beta plaques. It’s a departure from the popular hypothesis that the development of Alzheimer’s is sourced to the buildup of amyloid plaques outside of the cell.

The source of the issue, the scientists say, were lysosomes—molecular waste managers that were found to enlarge and fuse with autophagic vacuoles that failed to get broken down. These vacuoles then pool together in the nucleus of the most damaged neuron cells, where researchers subsequently found pockets of amyloid plaque.

To uncover this, the scientists ran five mouse models with Alzheimer’s and examined the relationship between issues in the lyosome-authophagous pathway and the identification of amyloid beta. What they found was that among a subpopulation of neurons, the broken autolysosomes—the merged version of autophagy and lyososmes during the degradation process—would accumulate in the center of the cell, bulging the plasma membrane outward. The bulging appears like flower petals blossoming out, causing scientists to coin the process and, subsequently, the impacted cells, “Panthos.”

But here’s the kicker: Further assessment of the central area where the autolysosomes pooled together found bundles of fibrils matching the size of amyloid beta. It’s a crucial piece of insight that describes how amyloid beta begin to take shape long before it starts to accumulate outside of the cell.

“Our results for the first time sources neuronal damage observed in Alzheimer’s disease to problems inside brain cells’ lysosomes where amyloid beta first appears,” Lee said in a statement. The acidification issues in lysosomes that tee off the dysfunctional decline resulting in Panthos were ultimately identified four months before amyloid beta deposited outside of the cell.

The new findings add to a growing body of evidence supporting issues with the cellular waste management process as a key sign of Alzheimer’s. Previous research from NYU Langone published in April linked the issues with the PSEN1 gene, while another study from 2017 highlighted how issues in lysosomes’ ability to travel within axons could be tied to early amyloid buildup.

The early indicator could have direct implications on future Alzheimer’s treatments, given many of the current mechanisms target amyloid beta deposits outside of the cell. Biogen’s Aduhelm, for example, is a monoclonal antibody that binds to amyloid beta peptides to promote amyloid removal. Eli Lilly’s donanemab works similarly but targets the amyloid deposits themselves rather than the peptide. The latest research hints these both may not be targeting the root cellular problem that results in Alzheimer’s. The team concludes that it anticipates “broad potential” of its research “to facilitate assessment of autophagy/lysosome modulators as therapeutic agents.”

“This new evidence changes our fundamental understanding of how Alzheimer’s disease progresses,” said study senior investigator Ralph Nixon, M.D., Ph.D. “[I]t also explains why so many experimental therapies designed to remove amyloid plaques have failed to stop disease progression, because the brain cells are already crippled before the plaques fully form outside the cell.”