Scientists have mapped the thymus, a gland in the chest that makes disease-fighting white blood cells, across the human life span. This “cell atlas” could help researchers understand how thymus cells change over time and how T cells develop, opening the door to new treatments for cancer and autoimmune disease.

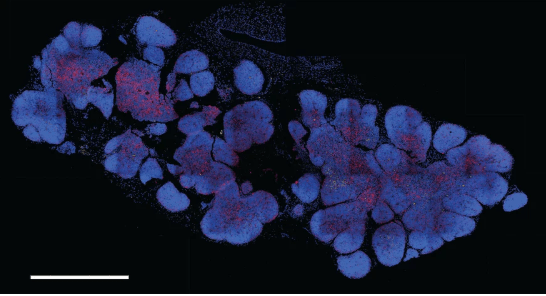

The scientists, from the Wellcome Sanger Institute, Newcastle University and the University of Ghent, used single-cell RNA sequencing to analyze about 200,000 individual cells from embryonic and fetal thymus glands, as well as from children and adults. Their findings shed light on where different cell types are found in the thymus as well as the many states in which they can exist.

“We identified more than 50 different cell states in the human thymus. Human thymus cell states dynamically change in abundance and gene expression profiles across development and during pediatric and adult life,” they wrote in the study, which appears in Science.

Using computational methods, the team mapped out how various kinds of T cells develop from their precursors in the fetal liver. From here, they figured out which signals tell immature immune cells what type of T cells they will become.

“With this thymus cell atlas, we are unravelling the cellular signals of the developing thymus, and revealing which genes need to be switched on to convert early immune precursor cells into specific T cells,” said Muzlifah Haniffa, Ph.D., a professor of immunology and dermatology at Newcastle University and a senior author of the study, in a statement. “This is really exciting as in the future, this atlas could be used as a reference map to engineer T cells outside the body with exactly the right properties to attack and kill a specific cancer—creating tailored treatments for tumours.”

In addition to improving T cell-based treatments, such as CAR-T cells for cancers, the atlas could make a difference for people with diseases characterized by the improper development of T cells, such as severe combined immunodeficiency, or by the turning of immune cells against the body’s own tissues, like Type 1 diabetes.

“We have produced a first human thymus cell atlas to understand what is happening in the healthy thymus across our lifespan, from development to adulthood, and how it provides the ideal environment to support the formation of T cells. This openly available resource will allow researchers worldwide to understand how the immune system develops to protect our body,” said the study’s first author, Jongeun Park, Ph.D., of the Wellcome Sanger Institute.

The thymus cell atlas is part of the Human Cell Atlas project, an international effort started in 2016 to map all cells in the human body as a resource for better understanding health and disease. Like the thymus cell atlas team, many of the collaborators focus on specific tissues, such as the spinal cord, lungs, heart and liver. Others are working on the “mapping” technology itself: single- and multicell profiling. All of the data, protocols and tools developed will be made freely available to the research community.