Scientists for the first time have accomplished long-term kidney transplants from pigs to primates using a clinically translatable immunosuppression protocol, a potential turning point in their quest to use animal donors to combat a long-standing shortage of transplant organs.

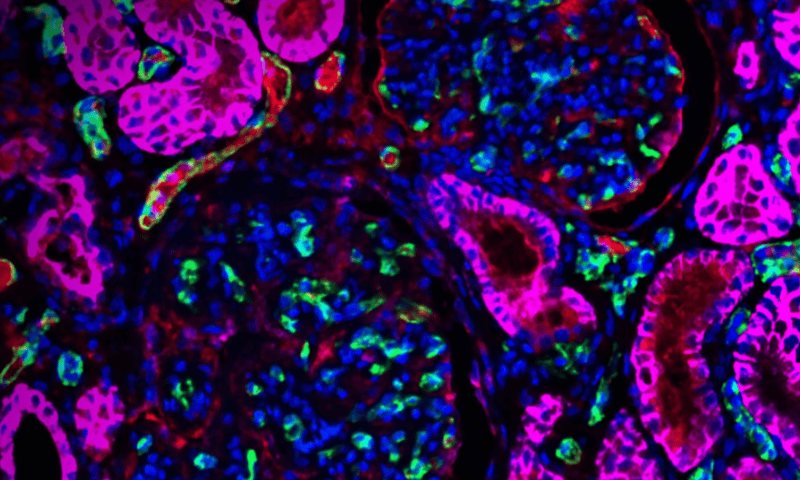

In a proof-of-concept study published Oct. 11 in Nature, researchers from transplantation biotech eGenesis reported that primates that received a single kidney from genetically modified pigs lived for as long as two years without rejecting the grafted organ. The kidneys functioned well enough to make up for both of the monkeys’ own being removed.

“These results are unprecedented and signify a monumental step forward toward achieving human compatibility,” Mike Curtis, Ph.D., president and CEO of eGenesis, said during a press briefing. “The ability to show long-term [pig] kidney survival in a non-human primate model … is a major milestone.”

Researchers have looked to pigs as potential organ donors for some time, but a flurry of progress in the last couple of years has brought the possibility of xenotransplantation—the transplant of an organ from one species to another—much closer to reality. The latest study comes on the back of a development in mid-August where researchers from the University of Alabama reported that pig kidneys transplanted into patients in a vegetative state could perform vital functions, such as filtering out chemical waste products. That followed a similar instance in 2021 when scientists attached a pig kidney to a human on a ventilator.

In those cases, the donor pigs weren’t altered to be free of porcine viruses or to prevent graft rejection, and the experiments lasted only as long as a week. But there is precedent for more enduring work, albeit with a different organ: In January 2022, a man with heart failure received a pig heart that had been genetically modified to keep his body from rejecting it. He died two months later when the organ failed. Researchers cited a “complex array of factors” as the cause. While a dormant virus in the pig tissue was potentially among them, notably, rejection by the patient’s immune system wasn’t.

Though the short time frames are a step in the right direction, the organs must last for far longer for such a treatment to be feasible in humans. To improve the pig kidneys’ staying power and prevent them from transferring viruses—a problem that, at least in theory, could have serious implications for public health—the eGenesis team used kidneys from donor pigs that, as an embryo, had undergone CRISPR modifications to 69 different genes.

Broadly, the edits fell into three categories: Knocking out genes associated with short-term transplant rejection, adding and overexpressing human genes that regulate important rejection pathways, and inactivating genes associated with porcine endogenous retrovirus, or PERV. While PERV is benign in pigs and has not been found to infect the recipients of pig organs, regardless of species, it’s known to infect human cells.

For comparison, the researchers also ran a set of experiments using kidneys from pigs that had only the knockout edits for avoiding transplant rejection. This would allow them to see how much adding the human genes and removing the ones for the virus contributed to the organ’s survival.

It made quite a bit of a difference. When the researchers engrafted the kidneys from the pigs with the transgenes and the knockouts into seven primates, the grafts survived for a median of 174 days. Meanwhile, the transplant recipients who received kidneys from pigs with just the knockouts—six of them total—lasted for a median of 24. All of the primates were on an immunosuppression regimen of induction therapy with B and T lymphocyte depletion, anti-CD154 antibody and mycophenolate mofetil, trade name CellCept. They were also given a short post-transplant course of tacrolimus, or ProGraf, and steroids.

There was also one major outlier: One of the transplant recipients with the full spectrum of gene edits survived for 758 days. Though this technically isn’t the longest a monkey has lived with a pig kidney, according to Curtis, it is the longest one has survived while on an immunosuppression regimen that could feasibly be replicated in humans.

“Longer survival has been achieved with much more aggressive suppression that really isn’t clinically translatable,” he said in the briefing. “The key here is that we’re achieving long-term graft survival with a clinically translatable suppression, which is incredibly important.”

There are ethical concerns about this kind of work. Writing in 2022 about the pig heart and kidney transplants into humans, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, or PETA, has called the developments “a tremendous waste of resources.”

“To talk about such procedures as though they were anything other than cruel—to animals and to humans waiting for organs—perpetuates the idea that xenotransplantation will someday be practical,” the organization wrote. “Presumed consent laws and preventative health measures will save more lives than these headline-getting surgeries ever will.”

Ethics are “front and center” for eGenesis, Curtis said. The company’s ethics review board focuses both on the treatment of the donors and the recipients, he noted, though he didn’t go into detail about the nature of the board’s oversight.

“These are incredibly important studies to enable this field and we take the ethics of it very seriously, and, of course, our main focus is to build a product that can help patients survive organ failure,” Curtis said.

From a safety perspective, the kidneys were well-tolerated by the monkeys, at least in this small study. This may bode well for eGenesis’ conversations with the FDA about moving the treatment into the clinic. The company has been in conversation for the past several years about studying their approach in humans, Curtis said. Now that the company has shown that the graft can survive for more than a year, they are “well on their way.”

“We will continue to work with the agency to enable a study in the near term,” he said. It’s likely that one of the company’s other programs in its portfolio, where pig organs are used as placeholders for human ones between transplants or during recovery from liver and heart failure, will get to patients first, as these don’t require as much long-term data, he explained.