An international study—the largest of its kind—has uncovered similar structural changes in the brains of young people diagnosed with anxiety disorders, depression, ADHD and conduct disorder, offering new insights into the biological roots of mental health conditions in children and young people.

Led by Dr. Sophie Townend, a researcher in the Department of Psychology at the University of Bath, the study, published today in the journal Biological Psychiatry, analyzed brain scans from almost 9,000 children and adolescents—around half with a diagnosed mental health condition—to identify both shared and disorder-specific alterations in brain structure across four of the most common psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence.

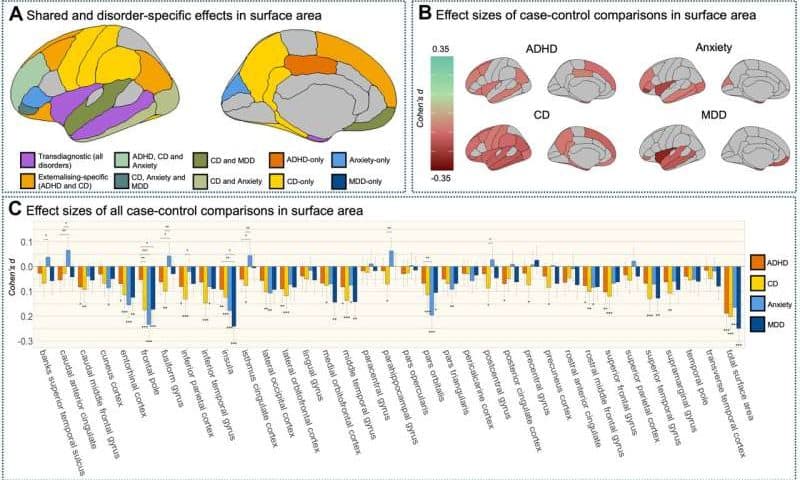

Among several key findings, the researchers identified common brain changes across all four disorders—notably, a reduced surface area in regions critical for processing emotions, responding to threats and maintaining awareness of bodily states.

Dr. Townend said, “Mental health disorders that start in childhood often go undiagnosed or untreated for many years—sometimes they are not recognized until adulthood. This places a major burden on individuals, families and society, and causes a huge loss of human potential.

“For these reasons, it’s important that we try to understand these psychiatric disorders early in a person’s life, and the ways they are similar to each other as well as how they differ from each other.”

The study involved 68 international research groups across five continents—all members of the ENIGMA Consortium, a global alliance of scientists working to understand brain structure and function through large-scale neuroimaging and genetic studies.

Why this study matters

The findings of this study challenge the traditional approach of studying mental health disorders in isolation. By identifying “transdiagnostic brain alterations,” this research opens the door to treatment strategies that target shared biological mechanisms across multiple conditions.

Dr. Townend said, “Our research shows that, even if they may look very different, the four most common mental health conditions of childhood and adolescence are very similar at the brain level. This suggests that we may be able to develop treatment or prevention strategies that are helpful for young people with a range of common disorders.

“This study helps us understand the common neurobiological threads that run through different psychiatric disorders in children and young adults. We now need to understand why the same brain changes might lead to disorders that seem very different to one another in terms of symptoms and behaviors.”

Study co-author Professor Graeme Fairchild, also from the Department of Psychology at Bath, added, “While previous studies have reported common alterations in brain structure across mental health disorders in adults, this is the first time that such findings have been reported in a large, international youth sample.

“Taken together, these results extend our understanding of the neurobiological basis of youth mental health disorders, which may help researchers and clinicians to target common biological processes across psychiatric disorders.

“This could be particularly important during childhood and adolescence as this is when many disorders first emerge, and it’s also a time when the brain is still developing and therefore interventions could lead to more lasting changes.”

Girls and boys: More alike than previously thought

The research team also found that girls and boys with the same mental health disorders seemed to show similar changes in brain structure (i.e. girls and boys with ADHD seemed to differ from girls and boys without mental health disorders in the same way). This was surprising given that previous, albeit much smaller, studies had suggested that girls and boys with the same disorder might show different changes in brain structure.

There is also considerable evidence for sex differences in the prevalence of these conditions, with ADHD and conduct disorder being more common in boys, and depression and anxiety being more common in adolescent girls.

Professor Stephane De Brito from the Center for Human Brain Health at the University of Birmingham, who was also involved in the study, said, “While we know that there are sex differences in the prevalence of those disorders, our study shows that this doesn’t seem to translate into differences in brain structure.

“At this point in time, while we can say that the brain is involved in all four of the disorders that we studied, it seems unlikely that these changes in brain structure can explain why there are important sex differences in the prevalence of these conditions. This means we might have to look at other factors such as the child’s early environment or experiences, which might interact with changes in the structure or function of the brain to increase risk for developing disorders.”