Stimulating the central thalamus during anesthesia sheds light on neural basis of consciousness

The brains of mammals continuously combine signals originating from different regions to produce various sensations, emotions, thoughts and behaviors. This process, known as information integration, is what allows brain regions with different functions to collectively form unified experiences.

When mammals are unconscious, for instance when they are under general anesthesia, the brain temporarily loses its ability to integrate information. Studying the mammalian brain both when animals are awake and unconscious could help to better understand the neural processes that contribute to consciousness, potentially offering insight into comatose states and other disorders characterized by alterations in wakefulness.

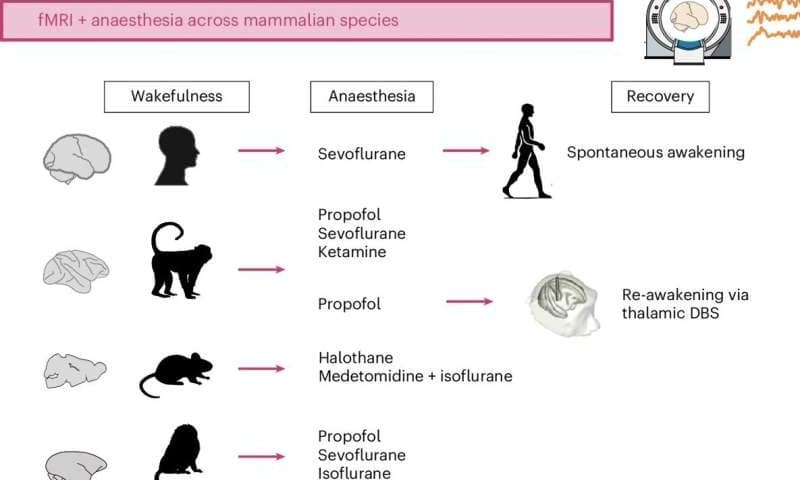

Researchers at University of Cambridge, University of Oxford, McGill University and other institutes worldwide set out to examine the brains of four different species of mammals during anesthesia. Their observations, published in Nature Human Behaviour, offer new insight into the brain regions and gene patterns associated with both unconsciousness and the regaining of consciousness.

“The paper is part of my research program on the neural basis of consciousness,” Andrea Luppi, first author of the paper, told Medical Xpress.

“For the last 10 years I have been pursuing this question. My earlier work focused on comparing what happens to the brain during the unconsciousness induced by general anesthesia, and during coma or other disorders of consciousness (such as what used to be called vegetative state).

“Our paper asks if anesthesia works similarly in the brains of humans, and of other species that are often used as models in neuroscience and clinical research.”

Switching the brain back ‘on’ during anesthesia

Luppi and his colleagues have been investigating the neural processes involved in conscious and unconscious states for almost a decade. Their recent paper focuses on four different animal species: humans, macaques, marmosets and mice.

“Our hope is that by studying different mammals and comparing them with humans, we may be able to narrow down on the most essential mechanisms of consciousness—and learn how to restore it in patients,” said Luppi.

As part of their study, the researchers measured the brain activity of humans and three types of animals they scanned while they were under general anesthesia, using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). This is a widely used and non-invasive imaging technique that measures brain activity by detecting changes in blood flow.

“Our approach allowed us to track over time how different brain regions interact,” explained Luppi. “We found that when humans and animals are awake, their brains are like a grand orchestra: though different brain parts play different roles, they are clearly all working together to produce the symphony. We call this ‘synergy.'”

The team observed that this orchestra-like collective activity ceases when all the animals they examined lose consciousness. However, they were able to restore it by stimulating the central thalamus, a region at the center of the brain that is known to relay sensory and motor information, but that may also be acting as conductor for the brain’s orchestra.

“The anesthetized brain is like a random assortment of instruments, each playing to its own tune regardless of what the others are playing,” said Luppi. “However, if you stimulate a small region deep in the brain, called the central thalamus, the animal wakes up from anesthesia—and the brain symphony is back.”

Using computational tools, Luppi and his colleagues modeled the connectivity between different brain areas and how different genes are expressed across areas, both while animals were unconscious and when they regained consciousness. This allowed them to identify neural mechanisms that play a key role in consciousness and that appear to be evolutionarily conserved across all the species they examined.

New insight into the neural roots of consciousness

This recent study improves the present understanding of how the brain restores wakefulness. In the future, the team’s observations could help to devise new treatments for disorders of consciousness that can emerge after brain injuries, infections or tumors, such as comatose, vegetative, minimally conscious and post-traumatic confusional states.

“Finding consistency across many species and many anesthetic drugs is important: what is conserved across evolution is often very fundamental,” said Luppi.

“Perhaps the most important contribution of our study is that we were able to build a computer model that predicts which region one should stimulate, to have the best chances of making the brain symphony-like again. This could be used for trying to identify which region one should stimulate in the brain of a chronically unconscious patient, to try and wake the patient up.”

Luppi and his colleagues are now planning further studies aimed at further exploring the neural mechanisms associated with a return of consciousness after periods of unconsciousness. Their hope is to ultimately inform the design of more reliable and targeted strategies to bring patients back from a coma or other prolonged unconscious states.

“My long-term goal is to understand the mechanisms that govern consciousness, and how we can use pharmacology or brain stimulation to restore consciousness in patients,” added Luppi.