Editas Medicine released a tiny drop of data last year as a proof of concept for its gene editing platform. Now, the CRISPR/Cas9 biotech will spend 2022 trying to back that up.

We’re going to hear more about EDIT-101, the gene editing company’s vision loss therapy, this year, according to executives who presented at the annual J.P. Morgan Healthcare Conference Wednesday.

In September, Editas reported some very limited data—and by that we mean a report on six patients—that pointed to improvements in vision for one patient with the retinal degenerative disorder Leber congenital amaurosis 10, or LCA10.

The company claimed at the time that its concept—and its treatment’s safety—had both been confirmed. But shares dropped amid questions about whether patients saw meaningful benefits from the treatment. The improvement in just one patient fell short of the improvements produced by a competing therapy from ProQR Therapeutics, analysts noted then.

Perhaps some of those questions will be answered, at least partially, when Editas releases more information from the phase 1/2 BRILLIANCE trial in the adult cohort this year.

We likely won’t hear any news for awhile from an ongoing pediatric trial in the same vision loss disorder, though. Editas is choosing patients for the trial carefully, specifically looking for children who are old enough to follow directions and able to handle all the required measurements to assess whether the therapy is working, said Lisa Michaels, M.D., executive vice president and chief medical officer.

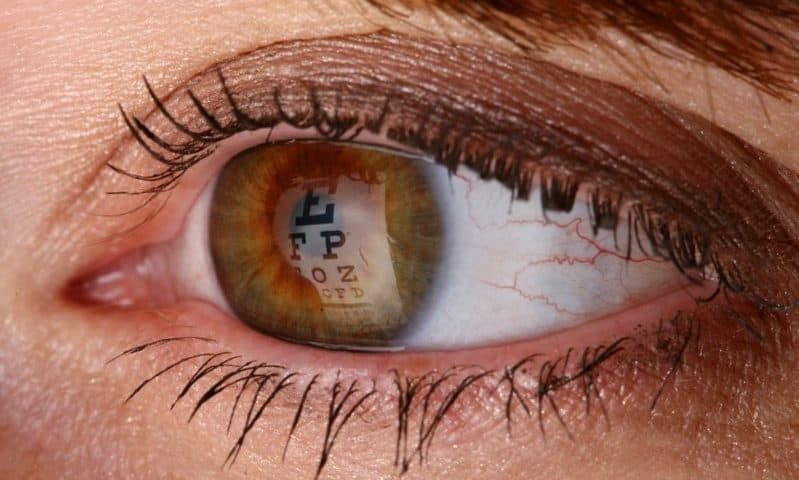

As Editas begins to think about a registrational trial for EDIT-101, one challenge is that the classical measurement for vision loss, called a best corrected visual acuity test, assesses whether a patient can read one line of text to another.

“The classic ‘can you improve your reading vision from one line to another’ isn’t really relevant in a patient population that can’t even read the chart,” Michaels said. “So we’re looking at a deep dive into the evaluation on how we can actually translate what’s being reported to us [from] the patients related to the outcomes that we’re measuring.”

Which is to say, Editas has not decided on what the endpoints may be for that crucial study. Chairman, President and CEO James Mullen said one of the company’s main objectives for the year is to figure out the goal to use in those future studies.

Editas will also move a candidate for retinitis pigmentosa through preclinical testing. Mullen expects that therapy to be “well advanced in IND-enabling studies” by the end of the year.

Another pipeline product, EDIT-301, is in studies to determine proof of concept for sickle cell disease. If Editas’ therapy shows some promise here, the company will have to really differentiate it, because the market is packed with entrants.

Mullen is well aware. “The bar is high for initial clinical outcomes,” he said, adding that what’s going to be important is longer-term data on durability and proof that EDIT-301 is safe over time.

Editas took some flak for releasing such limited data on EDIT-101 back in September. Mullen was mum on how long they’ll wait to report out initial sickle cell data, but did promise safety and engraftment data from the initial patients. The engraftment data would suggest the gene editing treatment was correcting the target gene.

Editas peer Intellia detailed a robust clinical program that included updates on a clinical trial for the rare disease ATTR amyloidosis in a presentation later Wednesday afternoon. Intellia beat Editas to the punch last year when it released first-in-human gene editing results.