There are hundreds of cell types in the human body, each with a specific role spelled out in their DNA. In theory, all it takes for cells to behave in desired ways—for example, getting them to produce a therapeutic molecule or assemble into a tissue graft—is the right DNA sequence. The problem is figuring out what DNA sequence codes for which behavior.

“There are many possible designs for any given function, and finding the right one can be like looking for a needle in a haystack,” said Rice University scientist Caleb Bashor, the senior author on a study published today in the journal Nature that reports a solution to this long-standing challenge in synthetic biology.

“We created a new technique that makes hundreds of thousands to millions of DNA designs all at once—more than ever before,” Bashor said.

How the CLASSIC technique works

The technique is called CLASSIC—an acronym for “combining long- and short-range sequencing to investigate genetic complexity.” It not only makes finding useful DNA designs (“genetic circuits”) much faster, but it also creates datasets of unprecedented scale and complexity—exactly what is needed for artificial intelligence and machine learning to be meaningfully deployed for genetic circuit analysis and design.

“Our work is the first demonstration you can use AI for designing these circuits,” said Bashor, who serves as deputy director for the Rice Synthetic Biology Institute.

CLASSIC could usher in a new generation of cell-based therapies, which entail the use of engineered cells as living drugs for treating cancer and other diseases. Demonstrating the approach in a human cell line also highlights its translational potential, since human cell-based therapies promise higher biological compatibility and the capacity to dynamically respond to changing disease states.

Kshitij Rai and Ronan O’Connell, co-first authors on the study, worked on the project during their time as doctoral students in the Bashor laboratory. Their work took four and a half years and involved “a lot of molecular cloning—cutting DNA into pieces and pasting it together in new ways.”

“We invented a way to do this in large batches, which allowed us to make really large sets—known as ‘libraries’—of circuits,” said Rai, now a recent doctoral alum about to embark on a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Washington in Seattle.

The team also used two different types of next-generation sequencing (NGS) techniques known as long-read and short-read NGS. Long-read sequencing scans long stretches of DNA—thousands or even tens of thousands of bases—in one continuous pass. It is slow and noisy, but it captures the entire genetic circuit at once. Short-read sequencing reads only a few hundred bases at a time but does so with high accuracy and throughput.

“Most people do one or the other, but we found using both together unlocked our ability to build and test the libraries,” said O’Connell, who is now a postdoctoral researcher at Baylor College of Medicine.

Building and testing genetic circuits

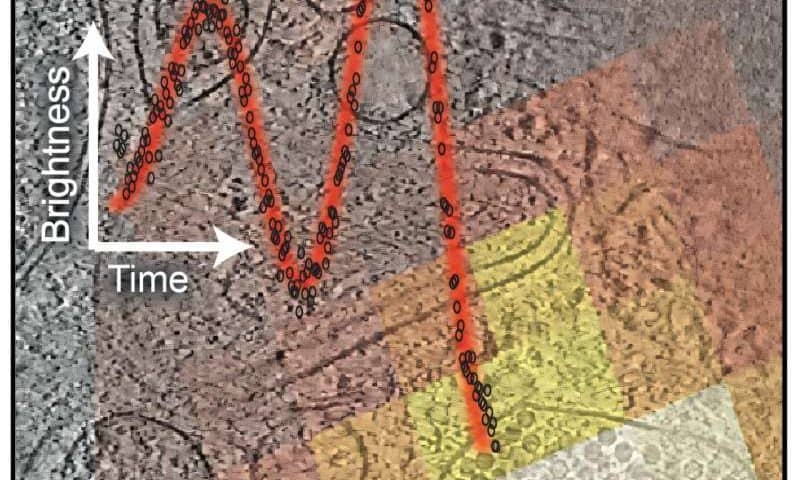

The Rice team developed a library of proof-of-concept genetic circuits incorporating reporter genes designed to produce a glowing protein, then used long reads to record each circuit’s complete sequence. Each of these sequences was then tagged with a short, unique DNA barcode.

Next, the pooled library of gene circuits was inserted into human embryonic kidney cells, where they produced a measurable phenotype with some cells glowing brighter while others expressed a dimmer glow. The researchers then sorted the cells into several groups based on gene expression levels—essentially how bright (high expression) or dim (low expression) they were. Short-read sequencing was then used to scan the DNA barcodes in each group of cells, creating a master map linking every circuit’s complete genetic blueprint—its genotype—to its performance, or phenotype.

“We end up with measurements for a lot of the possible designs but not all of them, and that is where building the ML model comes in,” O’Connell said. “We use the data to train a model that can understand this landscape and predict things we were not able to generate data on, and then we kind of go back to the start: We have all of these predictions—let’s see if they’re correct.”

Rai said he and O’Connell first realized the platform worked when measurements derived via CLASSIC matched manual checks on a smaller, random set of variants in the design space.

“We started lining them up, and first one worked, then another, and then they just started hitting,” he said. “All 40 of them matched perfectly. That’s when we knew we had something.”

Implications for synthetic biology and AI

The long hours spent poring over bacterial plates, cell cultures and algorithms paid off.

“This was the first time AI/ML could be used to analyze circuits and make accurate predictions for untested ones, because up to this point, nobody could build libraries as large as ours,” Rai said.

By testing such vast numbers of complete circuits at once, CLASSIC gives scientists a clearer picture of the “rules” that determine how genetic parts behave in context. The data can train ML models to analyze, design and eventually predict new genetic programs for specific targeted functions.

The study shows that ML/AI models, if given the right amount of training data, are actually much more accurate at predicting the function of circuits than the physics-based models people have used up to this point. Moreover, the team also found that circuits do not have just one “right” solution, but many.

“This is akin to navigation apps: There are multiple routes to reach your destination, some highways, some backroads, but all get you to your destination,” O’Connell said.

Another takeaway was that medium-strength circuit components such as transcription factors, proteins that bind to specific DNA sequences and control gene expression, and promoters, short DNA segments upstream of a gene that act as its on/off switches, often outperformed strong or weak variants.

“Call it biology’s version of ‘Goldilocks zones’ where everything is just right,” Rai said.

The researchers say this combination of high-throughput circuit characterization and AI-driven understanding may be able to speed up synthetic biology and lead to faster development of biotechnology.

“We think AI/ML-driven design is the future of synthetic biology,” Bashor said. “As we collect more data using CLASSIC, we can train more complex models to make predictions for how to design even more sophisticated and useful cellular biotechnology.”

The collaborative effort and expert perspectives

Both Rai and O’Connell said the collaborative environment at Rice made the work really enjoyable despite setbacks. Also, working with teams from other universities was a key ingredient for success. This collaborative effort included Pankaj Mehta’s group in the Department of Physics at Boston University and Todd Treangen’s group in Rice’s computer science department.

“I think a big part of what we did in this project is to show that while the same individual parts might not have any spectacular function by themselves, if you put the right combination of things together, it gives you these dramatically better genetic circuits,” Rai said. “That holds true for science as well. And that was the best part of this project behind the scenes—all of us bringing our different skill sets together.”

To help put the achievement of this research project in context, James Collins, a biomedical engineer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who has helped establish synthetic biology as a field, pointed to early successes such as the genetic toggle switch—a synthetic circuit comprised of two genes designed to repress each other’s expression; and the repressilator—a circuit of at least three genes that form a negative feedback loop where each gene represses the next, as historic reference points for the discipline which has now, with the Rice scientists’ work, reached a new defining milestone.

“Twenty-five years ago, those early circuits showed that we could program living cells, but they were built one at a time, each requiring months of tuning,” said Collins, who was one of the inventors of the toggle switch. “Bashor and colleagues have now delivered a transformative leap: CLASSIC brings high-throughput engineering to gene circuit design, allowing exploration of combinatorial spaces that were previously out of reach. Their platform doesn’t just accelerate the design-build-test-learn cycle; it redefines its scale, marking a new era of data-driven synthetic biology.”

Michael Elowitz, whose foundational work in synthetic biology was recognized by a 2007 MacArthur Fellowship for his design of the repressilator, said that “synthetic biologists have dreamed of programming cells by snapping together biological circuits from interacting genes and proteins.

“However, there is a huge space of potential biological components and circuits, and this dream has remained out of reach in most cases. Bashor’s work demonstrates how we can systematically explore biological design space and make biological engineering more predictable. In the future, it will be exciting to generalize this approach to other interactions and components, bringing us closer to making cells fully programmable.”